I’ve spent the last 30 years dealing with trauma and thinking about trauma, so while I was in Siem Reap, I felt a visceral need to do more than marvel at the ancient temples this area is so famous for. I wanted to do that yes, and I loved walking around Angkor Tom, Angkor Wat and several smaller temples–snapping pictures of the phenomenal carvings–but I also wanted to witness first-hand evidence of the killing fields and the war crimes of Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge. I’d read the memoir, First They Killed My Father, by Loung Ung, and seen the movie, The Killing Fields. The genocide suffered by the Cambodian people at the hands of their own people has haunted me ever since.

There was something about Cambodia that definitely didn’t make sense to me. It had a completely different feeling than Vietnam and Laos, both of which have done a lot of healing from the wounds caused by the American War. My first impression of Cambodia was that it felt discordant and broken to me. Siem Reap, where we were based, is a city designed to serve tourists and to reap tourist dollars. It was full of discos and restaurants and stores, massage therapists and a neon-advertised night market. Tuk tuk drivers hawking for a fare every two steps we took. There were bars aplenty. A Hard Rock Cafe. Gelato parlors. And lots of loud people out for a good time, from every country in the world. As one of our group members put it, “People go to the ruins by day and party at night.”

All the signs were in English and the streets were chaotic and loud. One of the first things we’d learned when we arrived is that dollars are the preferred currency; the Cambodian currency, the riel, is accepted – at an exchange rate of 4,000 riel for a dollar, but prices everywhere are quoted in dollars. Every menu, every shop, every massage parlor, even people selling on the streets are asking for dollars. There were children begging and selling trinkets at all the major tourist sites. Mothers thrusting their children out to sell more, to get more money. This, of course, was very painful to see.

Our neighborhood for our four-day stay in Cambodia is built up to serve the tourist trade going to Angkor Wat. But we learned out that it is actually the Vietnamese who own the temple concession – the $40 a head we paid for an admission ticket to the Angkor Wat and the other temples was lining Vietnamese pockets. That didn’t seem right.

The whole environment felt jangly and harsh and survival was in the air.

I felt such sadness from the moment I arrived in Cambodia. And it had to do with walking into an incredibly poor country where the entire population was decimated and traumatized less than 40 years ago. A huge percentage of Cambodia’s population is under 30; between 1975 and 1979, during Pol Pot’s regime, 1.8 million Cambodians died; they were violently murdered or lost their lives to starvation, illness or horrible conditions in work camps. When the Khmer Rouge took over in April of 1975, families were separated immediately. Babies were killed, young boys and girls, seen as blank slates that could be programmed into the Khmer Rouge philosophy, were trained to be soldiers, to kill, to report their parents for the slightest infraction. Anyone with an education of any kind was immediately killed or if they “were lucky,” were sent to work in sub-human conditions, fed two spoonfuls of rice a day while doing back-breaking physical labor for more than a dozen hours a day.

I’ve only been here a few days, but I can see that many Cambodians are still too traumatized to talk about this part of their recent history. Their culture is a reticent one; you don’t talk about what you feel or what happens inside your home. Parents who lived through the Khmer Rouge years generally find it hard to talk to their children about what they suffered, and many people want to forget and move on. But as someone who has studied the long-term impact of trauma for decades now, I know that forgetting or trying to forget doesn’t heal trauma. I was interested and wanted to learn more.

One day, I stepped away from the planned tour activities with Joanie and Joanne and the three of us rented a tuk tuk ($30 for 7 hours) to take us to three sites that talk about the Pol Pot genocide and the impact war has had on this nation. I knew I’d be missing some amazing sights and that I’d lose the chance to learn about the ancient history of the Khmer people, but I felt compelled to discover what I could about Cambodia today–and the impact war and genocide has had on this struggling nation.

Our first stop was way out in the country at the Landmine Museum. On the drive out there, in our open-air carriage pulled by a motorcycle, we saw lots of local life along the way.

Skinny cows (they come that way, our Cambodian guide Nom had told us) and chickens wandering everywhere. A woman squatting, cooking in a huge wok by the side of the road. A bicycle with a huge load of firewood on the back. A factory making brightly colored shrines which mark every Cambodian home to keep away bad luck. Sewing shops. A cement factory. A woman doing wash by the side of the road. Kids playing, not in school. Kids working alongside their parents at every possible task. Kids in school uniforms. Firewood companies. Gasoline and beer sold in bottles by the side of the road. Government workers in green uniforms clearing the algae from the water moat surrounded Angkor Wat. A tuk tuk with a motorcycle in the front and a cart overflowing with coconuts on the back. A man sat on top of the huge load, talking on his cell phone. In this impoverished country, cell phones are everywhere.

Half the people we passed riding in tuk tuks were wearing face masks. Hammocks by the side of the road with people sleeping or resting inside. A wedding with brightly colored gold and orange canopy with music broadcasting out to the whole community. Roadside stands selling fried crickets, silk worms, spiders and cockroaches. Stretches of tourist oriented shops selling the same fake silk scarves, hats, wicker baskets and flip flops. We loved the breeze and the countryside passing by. And then about 45 minutes out of the city, we came to The Landmine Museum.

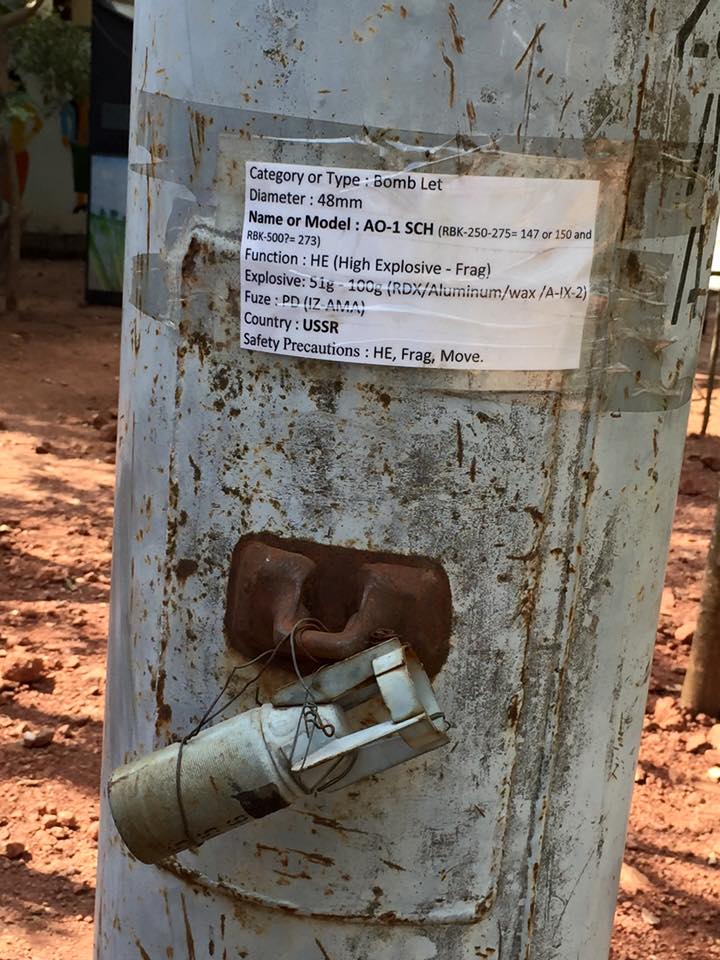

The Landmine Museum is a private museum that exists to tell the story of landmines in Cambodia. Over the course of thirty-five years of war, 26 million landmines and sub-munitions were dropped over Cambodia. Between 1965 and 1973, the United States alone did 65,000 bombing runs over Cambodia, dropping a staggering 2,700,000 tons of bombs.

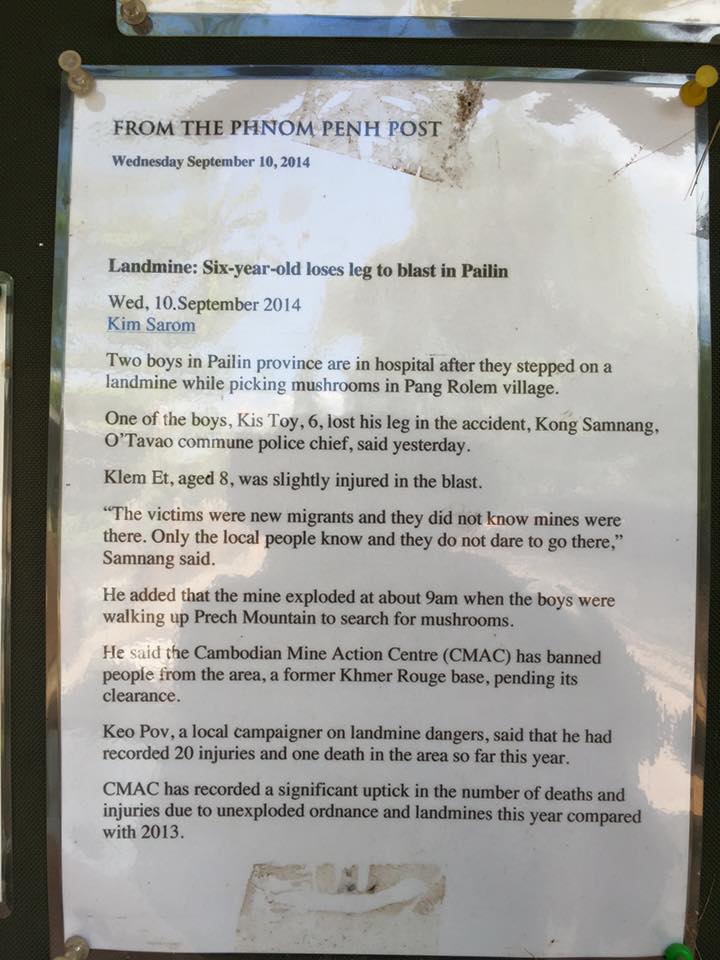

At least three million tons of these bombs, artillery rounds, mortar rounds and rockets did not explode when they landed. These unexploded landmines and bombs stay active forever, and have been responsible for maiming and killing tens of thousands of Cambodians, many of them farmers and children. Some people have survived these explosions and some have not. This is the subject of this museum.

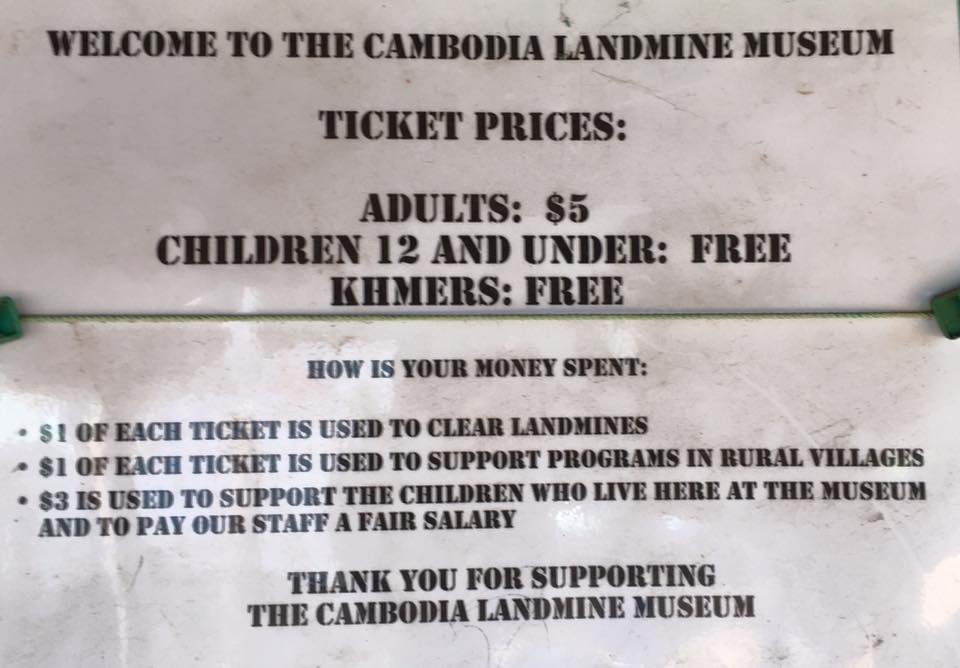

As we walked up to the entrance to pay our $5 entry fee, the pathway was bordered by U.S. bombs. That was the I grew quiet inside. I knew this was something I wanted and needed to see. I picked up an audio tour (produced in excellent English) and slowly made my way through the exhibits.

Turn your images on if they aren’t already…story continues in between the pictures below:

US bomb #1

US Bomb #2

US bomb #3

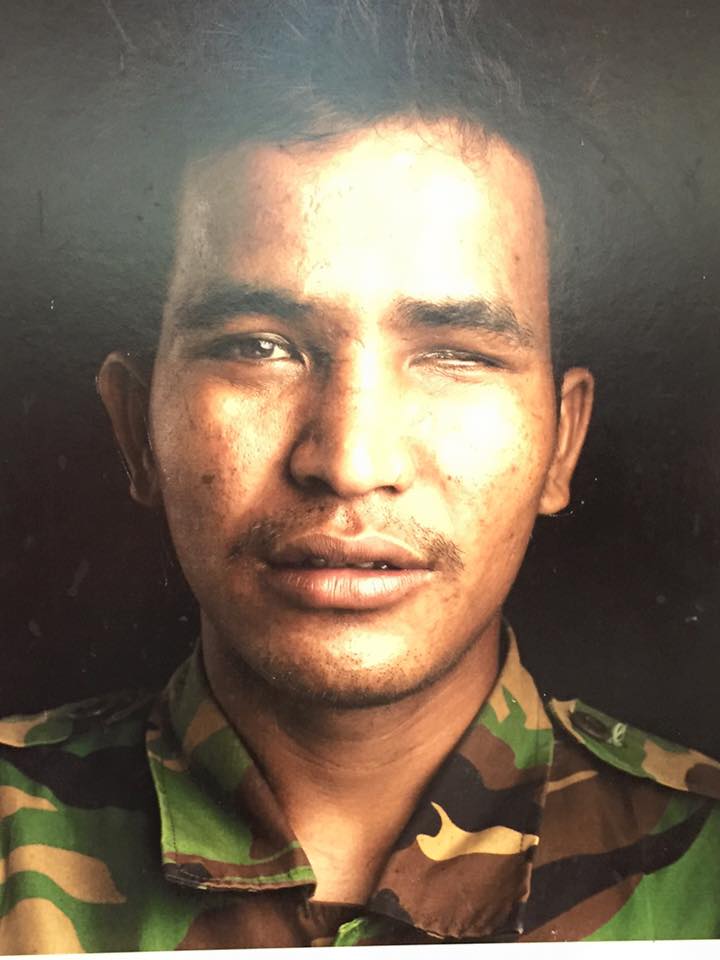

The Landmine Museum was founded by Aki Ra, who was named their 2010 hero by CNN. (You can watch the award ceremony and a beautiful speech introducing him here.) Aki Ra’s parents were murdered when he was a small child during the Khmer Rouge regime. At five he was put in a children’s work camp, and by the age of 10, he was given his first gun and taught to kill.

He says, “The gun was an AK-47 and it was more or less the same size as me so I had a hard time finding a way to carry it over my shoulder. It took me a little time to get used to its weight and the kickback when I fired it. The Khmer soldiers laughed at me as I struggled to learn how to handle it. I learned to shoot by aiming at fruit in trees, small animals and fish in the rivers. The Khmer soldiers had a huge pile of guns and would let us choose which ones we wanted to use: AK47s, M16s, or M60s. Also I could use rocket launchers, mortars and bazookas.

“In a way, these weapons were like toys to us children and we used to play games with them. Some small children were not familiar with guns and the Khmer Rouge would give them loaded guns with the safety pin off. One of my friends shot himself in the head accidentally because he did not understand how the gun worked.

“Rocket launchers and mortars were actually easier for me to use because we would be lying down as we fired them and would not have to support any weight, as we would have to with a machine gun.”

Aki Ra spent the next two decades as a soldier, first for the Khmer Rouge and later he defected and fought for the Vietnamese. He talked about defecting to the Vietnamese army when he was still a boy: “As I was one of the newer soldiers in my unit, I was required to go out at night and hunt for food. We hunted with our regular weapons, AK-47s or M-16s. When I would go into the jungle to hunt I would sometimes run into my friends from the Khmer Rouge, children like myself, who I had grown up with, who were hunting for food to eat.

“We would hunt together and when we were through, play together.

“The next day we would kill each other.”

During his 20-year career as a soldier, Aki Ra set thousands of landmines. “Landmines became my best friend. They protected me, helped me find food, and saved my life on numerous occasions when the war was at its fiercest.”

After his time as a soldier, killing and setting landmines, Aki Ra began to travel around Cambodia, wherever a village requested him to go, to defuse land mines. It was extremely dangerous work. Many people were killed trying to scavenge the metal in landmines for scrap. But Aki Ra had been working with landmines for decades and was very careful and he made it his personal mission in life to clear landmines and unexploded bombs. He did it alone for many years.

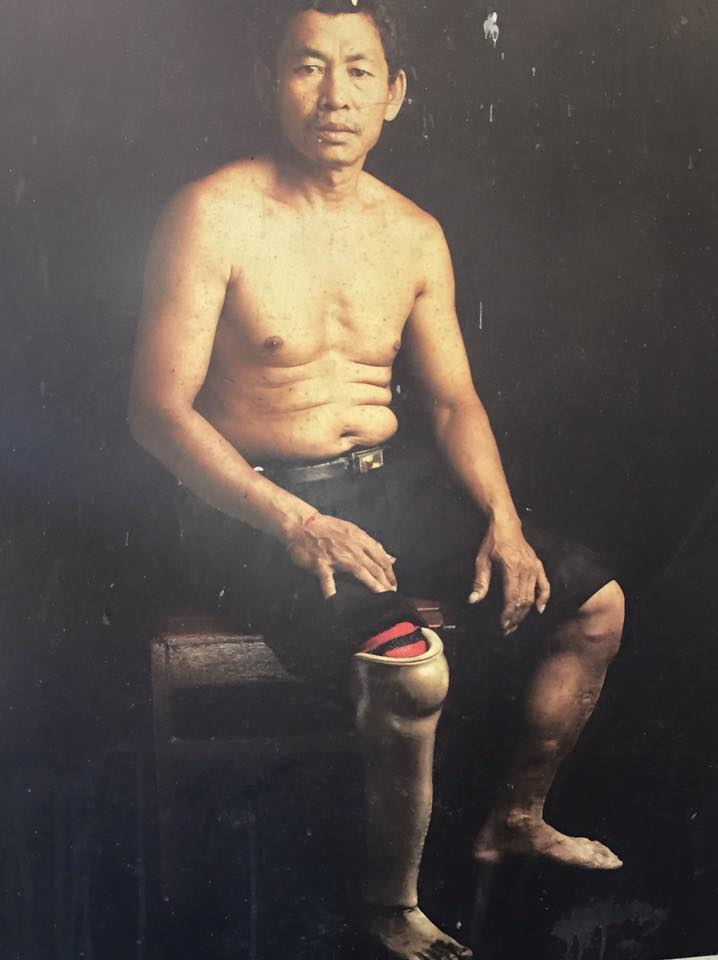

When he began, in the 1990s, there were thousands of injuries and deaths from landmines every year; by 2014, this number had been reduced to 157, but still there was this staggering statistic: 1 out of 3 people in Cambodia is a landmine victim.

Prostheses for land mine victims

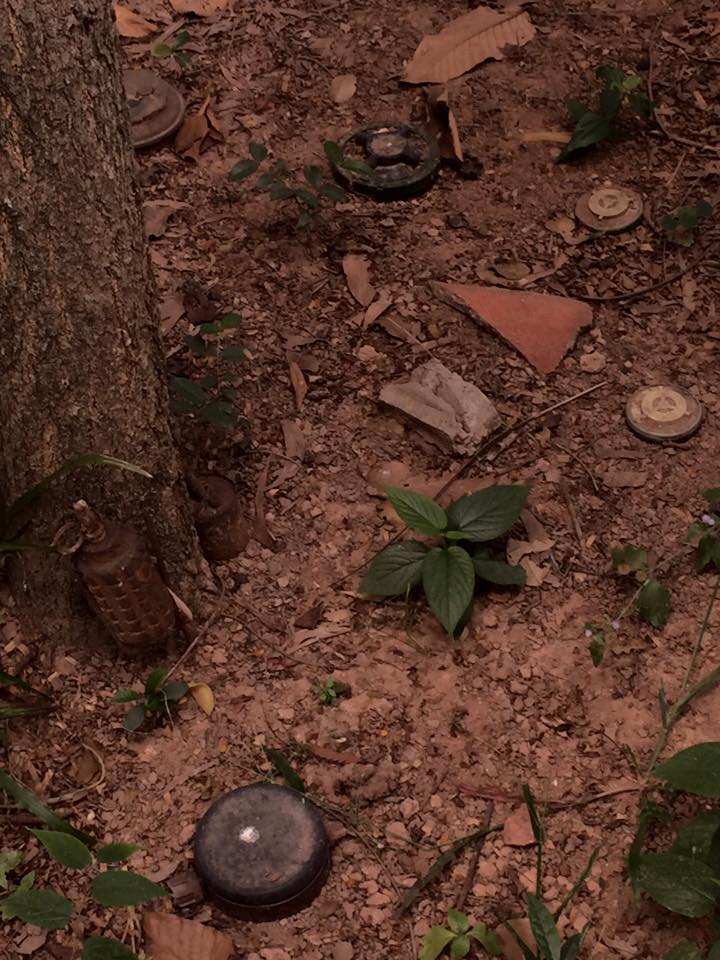

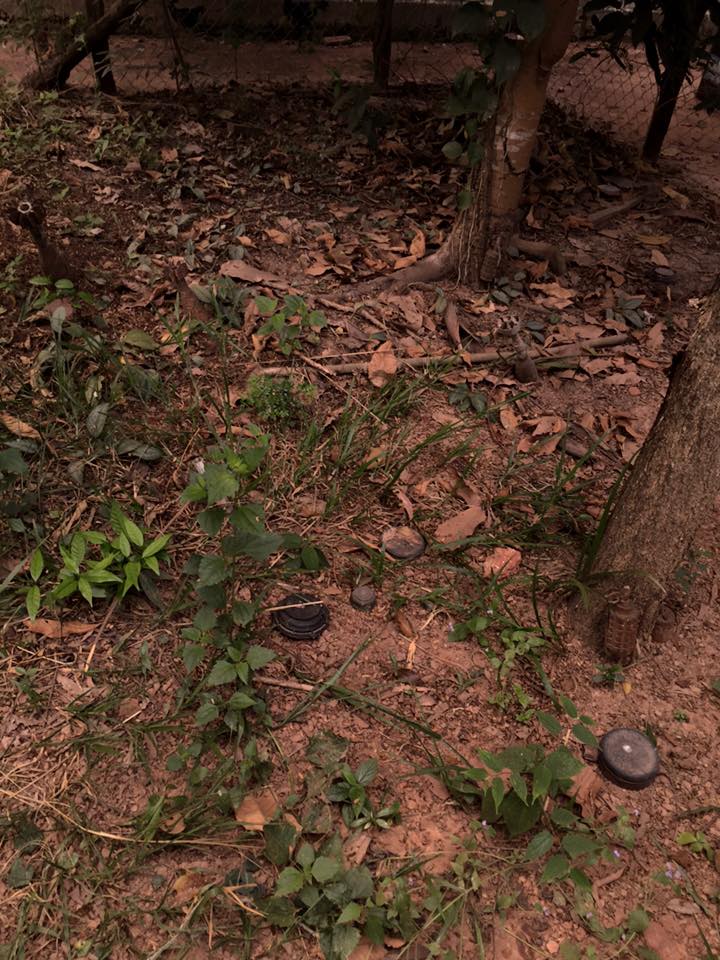

Aki Ra, who helped to create the problem during his time as a child solider, has personally cleared tens of thousands of landmines, and many of them are on display at his museum:

Only a tiny percentage of the land mines Aki Ra has cleared

Aki Ra is now part of an officially sanctioned demining team, using specific methods to defuse mines. Rather than disassembling them as he used to do, they now find active mines and explode them in place.

Mine defusing outfit

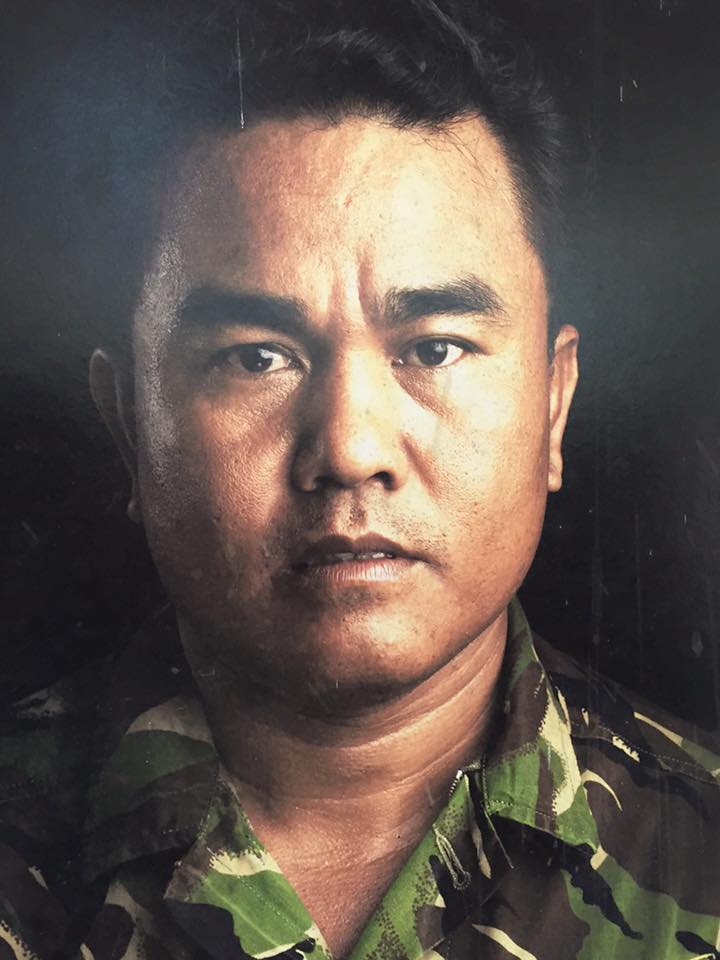

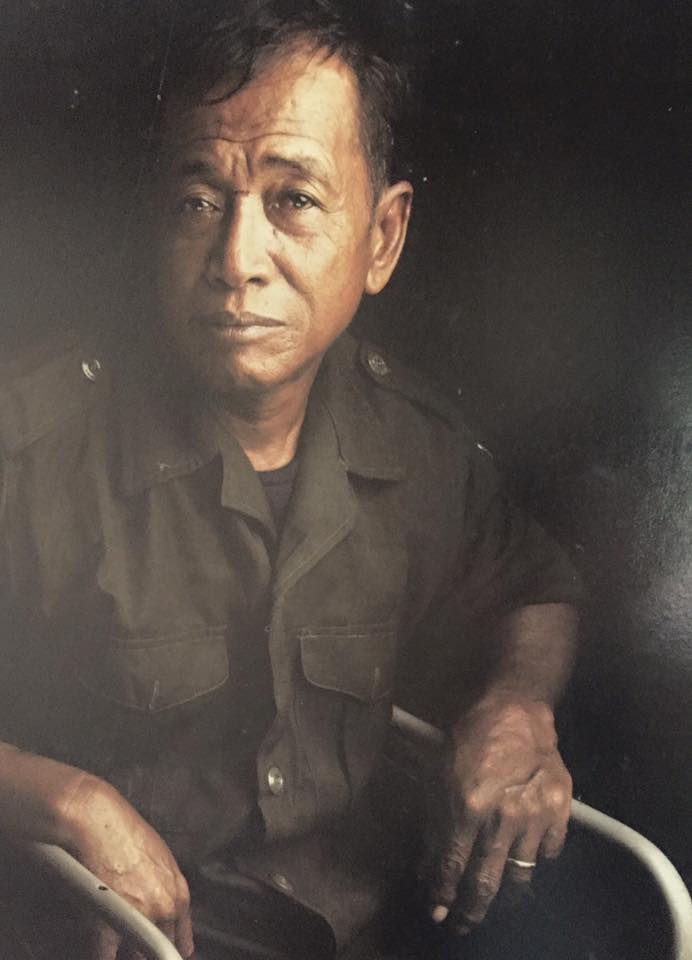

Here are some of the members of the demining team:

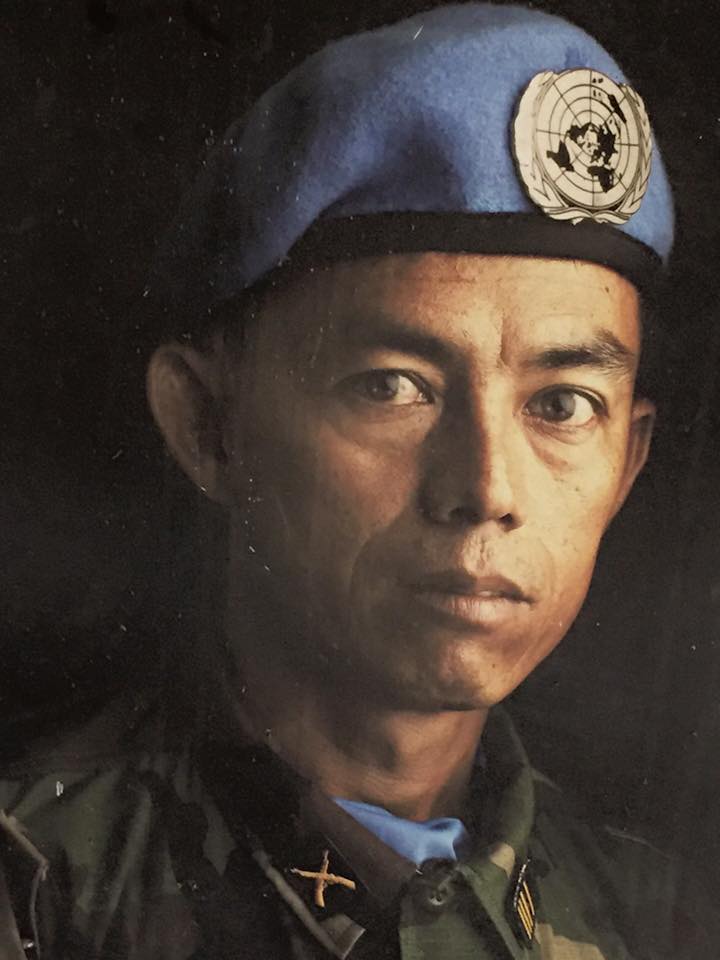

Aki Ra

It will take years to clear all that remain. Landmines and bombs have been found on the sides of roads, in the middle of villages, behind houses, police stations, and scattered across farmland across the country. Here’s what they lo0k like:

This and the next two pictures show what land mines look like in a field

Every day, Aki Ra and his team of deminers (Cambodia Self-Help Demining) are working to lower the number that remain. Between November of 2008 and March of 2015, CSHD has cleared 98 villages and 2,700,000 square miles of land.

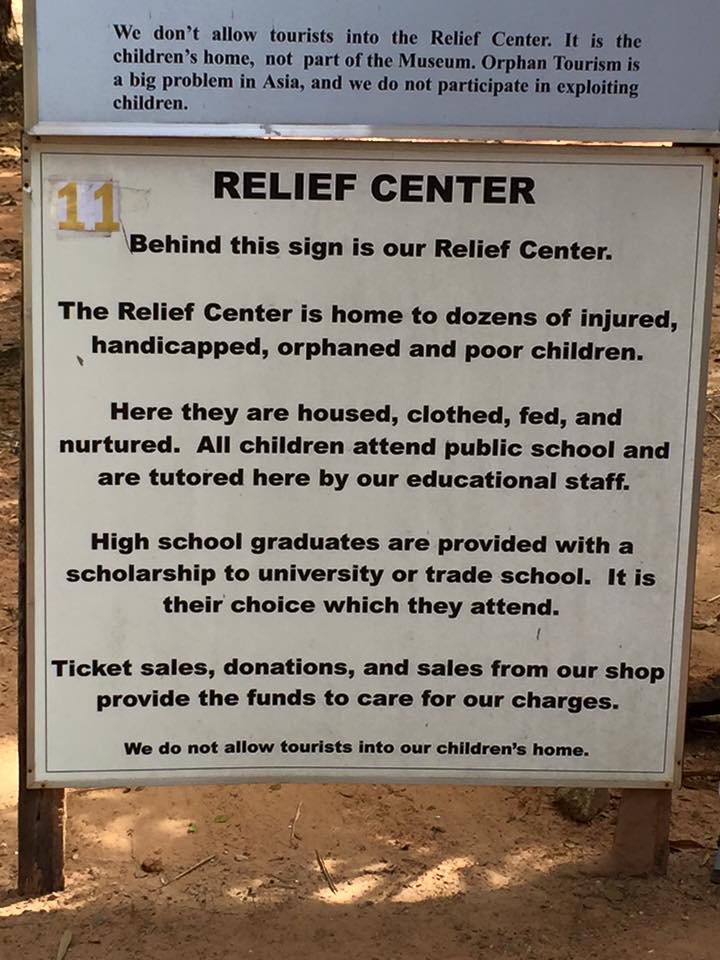

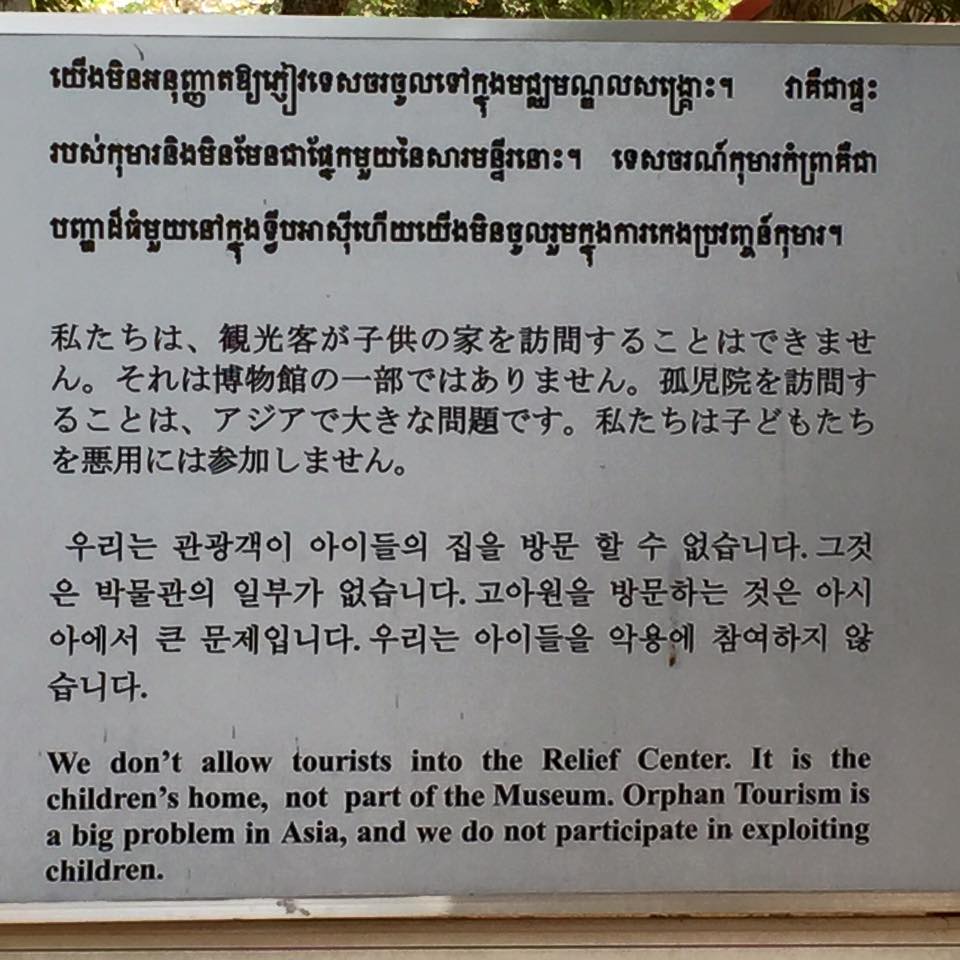

You might think this was enough for one man. But Aki Ra didn’t stop there. He has also brought child landmine victims into his home and given them a place to live, medical care, and an education. Behind the Landmine Museum these is still a center that takes in disadvantaged kids.

I’m including below a few of the essays they wrote about their life experiences. After reading their stories, I hope it will be a very long time before I ever complain about my own problems in any way.

Another section of the museum talked about landmines all over the world. According to the Land Mine Monitor, the three countries thought to still be actively using landmines in 2014 are Myanmar and Syria. And the countries still manufacturing them? Myanmar, Pakistan, India and South Korea. And the United States is still not fully in compliance with the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban treaty.

In an outdoor display, individuals from all over the world were profiled–people who’d had the courage to save other people’s lives by standing up during times of war and genocide: people who hid Jews during World War II, people who hid people during the war in Bosnia and Croatia and during Pol Pot’s regime.

It was one of the best five dollars I’ve ever spent.

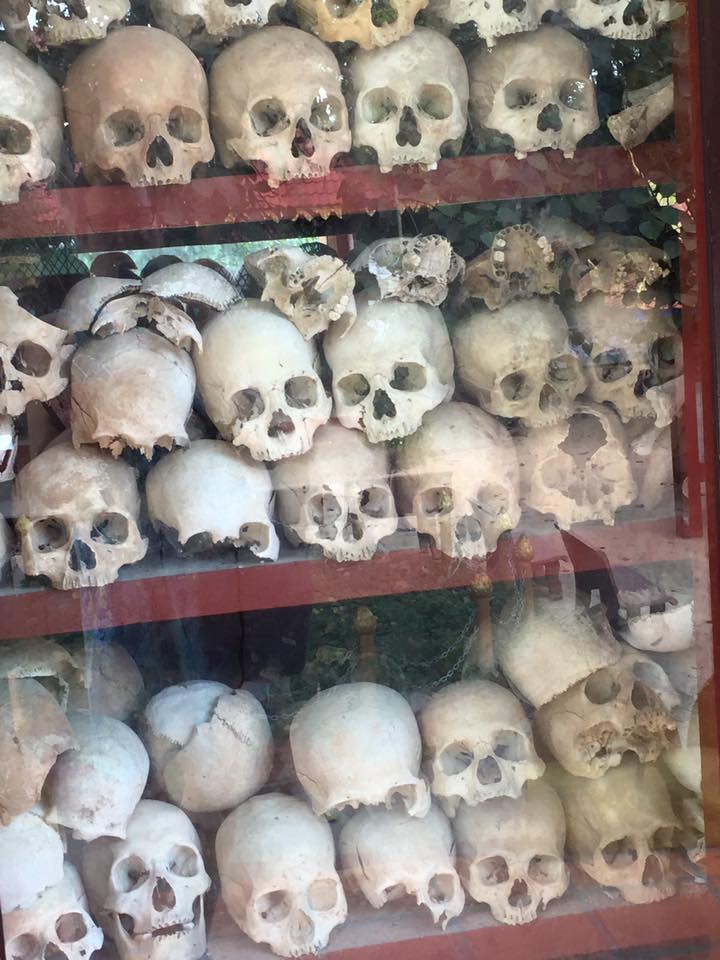

After the Land Mine Museum, we asked our driver to take us to Wat Thmey, a Buddhist temple built on the site of a former killing field. In the center is a pagoda full of just a tiny portion of the bones and skulls of the 2 million Cambodians who died under Pol Pot’s regime. This in and of itself was deeply disturbing. As are some of the images that follow:

Skulls in Pagoda at Wat Thmey

Killing Fields Victims

Tribute

Buddha watching over all

These were some of the exhibits on placards around the property:

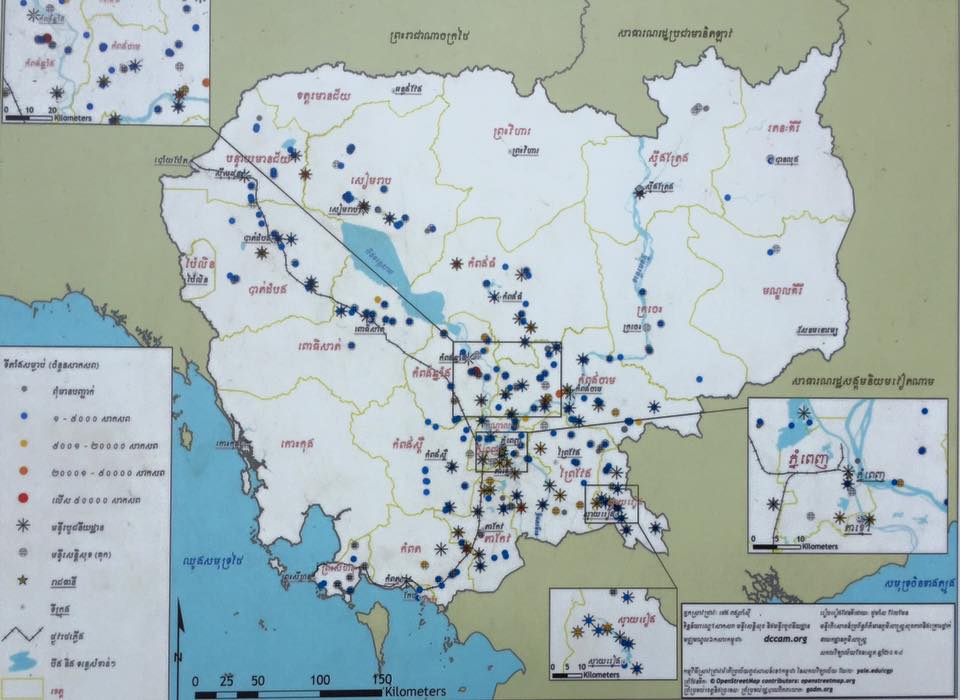

Known burial sites–killing fields throughout Cambodia

“After January 7, 1979, exhausted and traumatized survivors return to their homes to start life anew with the belongings they are able to carry. The survivors were unaware of the fate of their family members, many of whom died during the Khmer Rouge regime.”

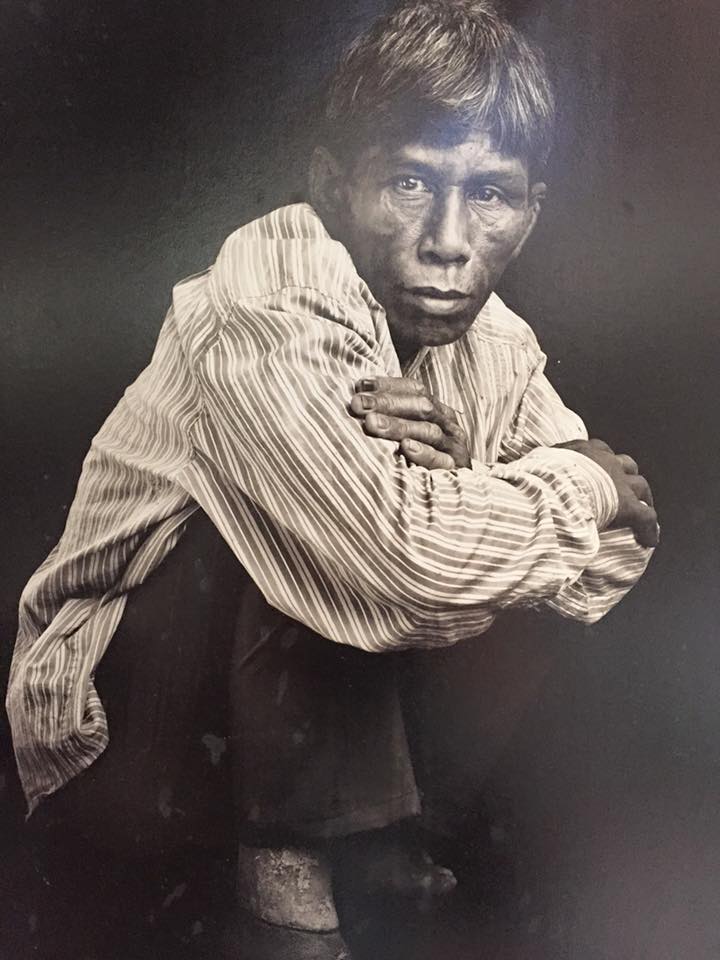

Child soldier

I’d read on Trip Advisor not to miss the exhibit of paintings of one survivor’s life that were tucked away somewhere on the grounds of Wat Thmey, but the review said they were completely unmarked and very hard to find. So I knew I was looking for them. I tiptoed around to the edge of the monk’s quarters – to find sleeping monks and orange robes hanging out to dry, but that area was off-limits so I turned around.

I went back and asked our tuk tuk driver if he knew where it was. He didn’t, but he asked the old women at the ubiquitous tourist concession, selling the same scarves and balloony pants you see everywhere. They spoke back in rapid Cambodian and gestured. He told us which way to go and we found the room. We never would have found it if he hadn’t intervened.

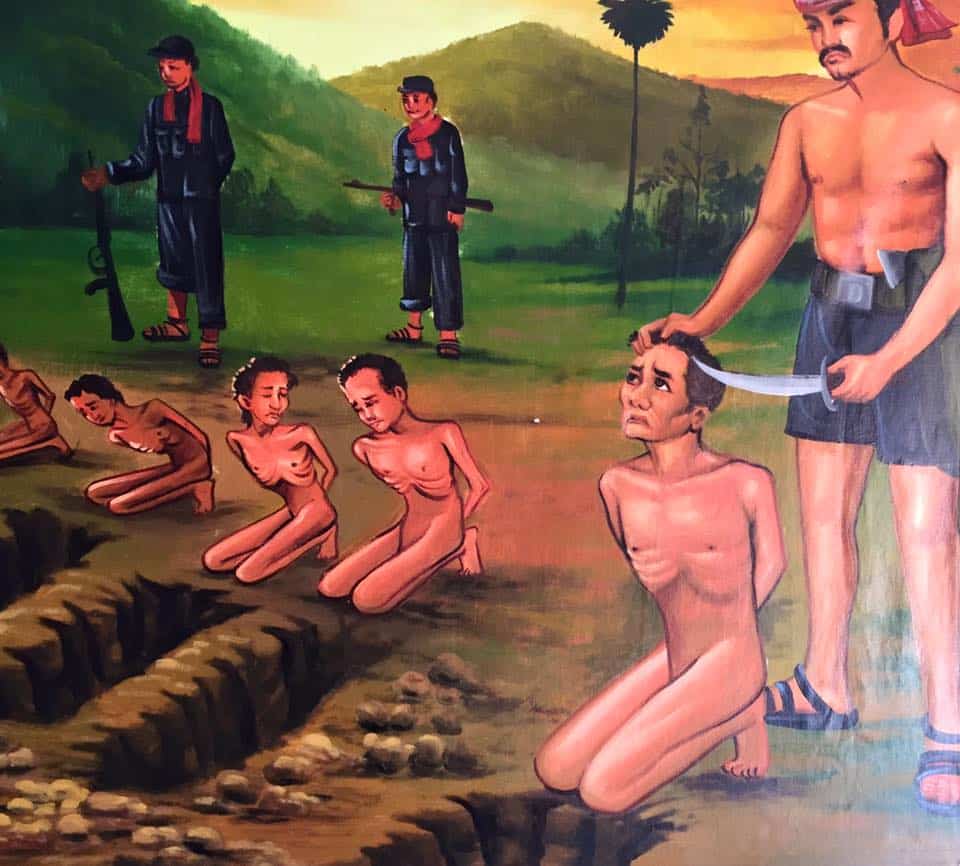

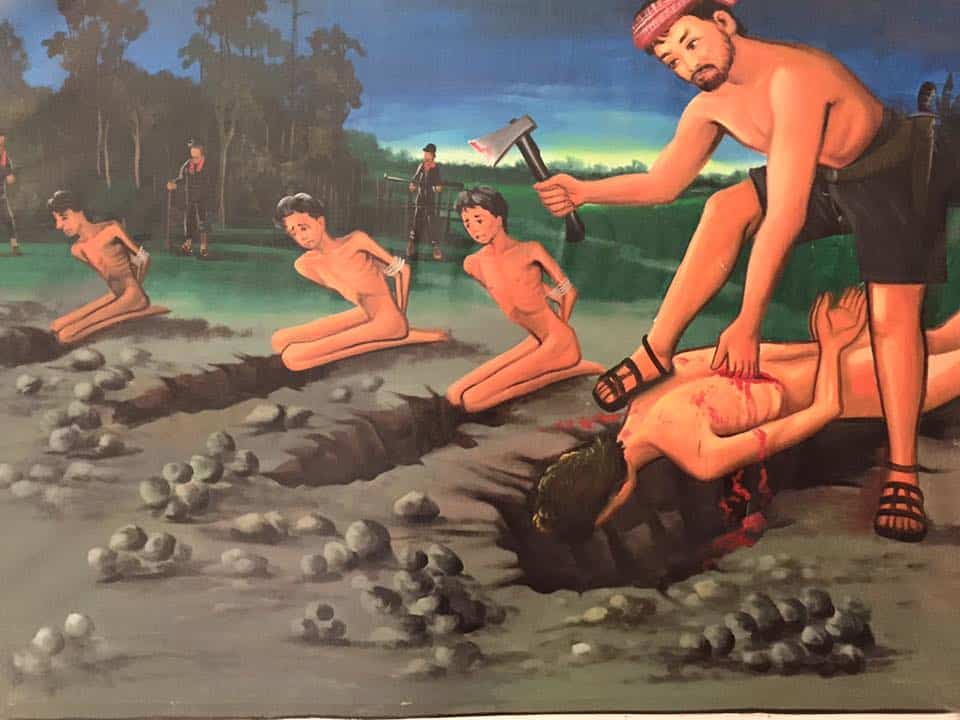

The gallery contained 21 very vivid paintings of the torture committed by the Pol Pot regime. Seeing that exhibit was one of the hardest things I’ve ever seen.

The first panel, introducing the exhibition, read, “First of all, we would like to say a special thanks for visiting Cambodian historical photo museum which was inaugurated in December 2013. Story that will be being told to the next generation about LIM Saromi’s real life. He was forced to work as an assistant in Pol Pot’s prison where he saw the most brutal kill. Sometimes, He himself was badly tortured and almost killed. But luckily he survived again and again. This is a real story which should not have happened.”

I’m not sure why I felt compelled to bear witness to this collection of horrible and graphic images, but I did. I felt I had to. Their suffering and the cruelty of the Khmer Rouge deserved being witnessed.

Here are three of the terrible paintings:

“Mr LIM Sarom was survived from execution because of he escaped from the accusation of intending to join the resistance movement of Khmer rouge regime. However, he was offered an unexpected job which served as an assistant of killer. His duty was to dig grave and bury bodies, so he witnessed the killing. Prisoners were tied up their hands behind their back, forced to knees down in front of grave. The killers beat in prisoners’ head with axes. Those who were beaten convulsed and fell into the grave. The one who dug grave must refill those graves.”

The final stop on our “war tour” was the War Museum, a site full of tanks, airplanes and other artifacts of war. The most compelling thing was our guide, who spoke so fast and in such a monotone that it was hard to glean his English, but already knowing some of the story, I was able to get about 80% of what he said. He talked about the suffering of his own family, he told us that the people were starved because hungry people only think of food and never fight back, he told us that people with eyeglasses were killed right away because they were thought of as intellectuals. And that babies were murdered so their mothers would keep working in the fields. That even elephants had plastic prostheses. And how landmine victims who couldn’t afford to pay for their own treatment died waiting outside of hospitals.

He said all of this in a rote expressionless voice and I just kept breathing. And we gave him a big tip on our way out. He gives these tours as a volunteer. I know how much telling the story can begin to heal trauma – maybe that is why the guides at this museum lead tourists around each and every day.

It is only 16 years since war ended in Cambodia, and everyone over the age of 40 lived through Pol Pot’s regime.

It was a hard day, a grueling day, and perhaps it isn’t something most tourists want to see, but I needed to and I was glad I did. Somehow it put into context so much of what I’d seen in Cambodia. They say it takes seven generations to fully heal trauma – the healing has just begun.

Our wonderful tuk tuk driver, “Mr. Mesa.” We gave him a twenty dollar tip and took him out to lunch.