August 6, 2025

Today, I arranged to go on a three-hour trek through the rice fields on the other side of Sidemen. My guide, Gus Tanggi, says that at 43, he’s the youngest farmer around. He works his plot of land part-time when he’s not being a guide for people like me. He knew the area we hiked through intimately; it included his fields and his home. As we walked, Gus seemed to know everyone; we stopped often while he chatted with his neighbors. I couldn’t understand their Indonesian, but it was obvious that Gus lives in a tight-knit community with his wife and three children, aged 11, 9 and 4.

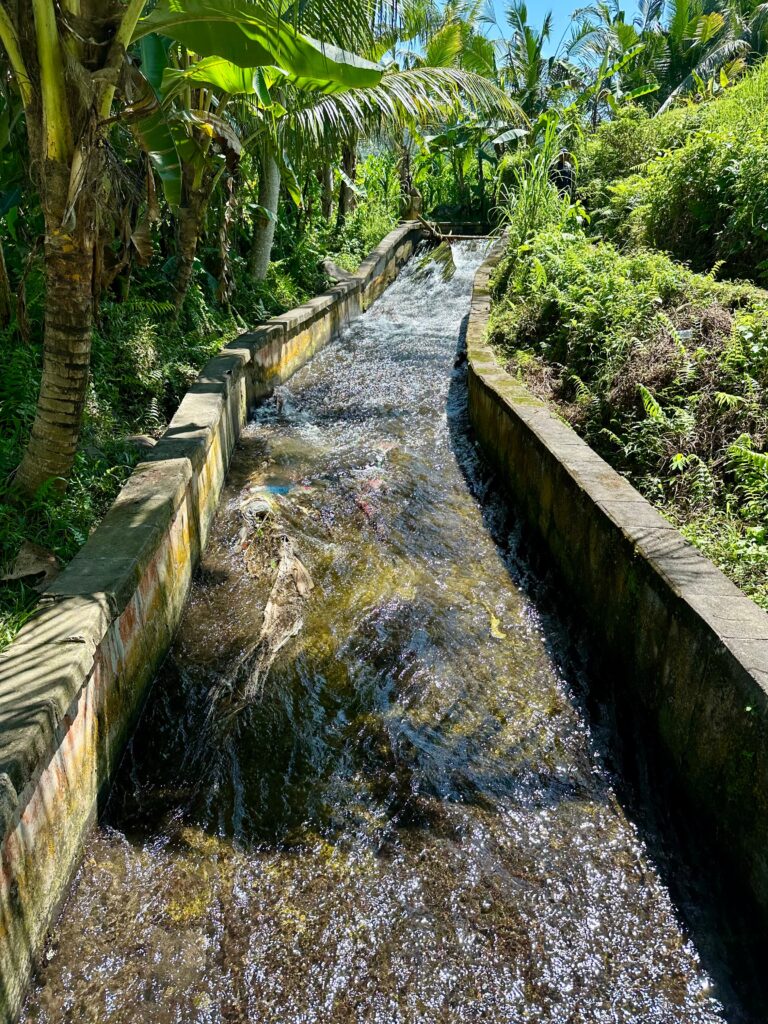

As we passed through the fields, we walked along narrow ledges on either side of the irrigation channel that irrigates the fields.

This is what the channels look like. Mostly, we walked on the ledges on either side.

Sometimes the stone edges gave way to mud or dirt or steps. Whenever our footing got gnarly or the path grew slick with mud, Gus held up his arm for me so I could grasp his strong forearm for balance. He seemed to know exactly when I needed a little help. Mostly, I just had to focus and watch my steps carefully. And stop fully every time I wanted to take a picture.

There was so much beauty everywhere. I just had to keep stopping.

I loved these tools in a field:

All of it was blessed. This was an offering on the edge of one of the fields we crossed.

Unfortunately, there was also a lot of garbage strewn on the ground. Bali was never a plastic culture until plastic was introduced by westerners, so they are catching up on the infrastructure to deal with it.

As we walked, it was common to see farmers carrying huge loads on their heads.

What I learned from Gus today is that only old people farm in Bali anymore. Some of these old people have been farming all their lives; others have worked other jobs—teaching, building, tourism—and when they retire, they return to their villages to farm.

Gus told me this man is the oldest farmer he knows. He’s 105 years old and is out here everyday.

“If we keep farming,” Gus told me, “we’ll never bring our lifestyle up.” If the Balinese don’t own their own land, their option it to work a small plot for the landowners, those who’ve had land passed down through the generations. The margins are tight, the profits so small, and climate change has made farming more unpredictable than ever.

These magnificent fields are planted on a rotating basis—half a year of rice, and half a year of a combination of Bok choy, sweet potatoes, chilis, peanuts, long beans, taro, tapioca, corn, and flowers for offerings. When the fields are planted with rice, the owner of the field gets 60% of the profit and the farmers get 40%. When other crops are planted, the owner gets 30% and the farmers get 70%. And the farmers can keep the profit for anything extra they can grow along the sides of the main rows.

If you don’t own the land, it is very difficult to earn a living as a farmer in Bali.

And when there aren’t enough farmers, the owners plant trees instead: vanilla, coconut, mangosteen, because they require much less tending.

Gus told me that young people don’t want to farm in Bali; if they’re going to do farm labor, they go to Australia or Japan where they can make much more money. Gus said the income for a Balinese farmer is 200,000-300,000 rupiah a month, less than $20 dollars a month. In Australia, a farm worker picking fruit can earn that much per hour; in Japan, substantially more.

Yet working on farms isn’t what young people in Bali want to do. For many, their highest aspiration is to work on cruise ships—that’s where the real money is. Balinese young people can earn $800-3000/month plus tips on a cruise ship, enough money that if they go out for 6-8 months on a ship, they can come home and buy a piece of land. Then they can go out for another 6-8 months, come back and build a house. Then they can go out for another 6-8 months and buy a car. After six-eight times, they have enough capital to start a business.

Gus Tanggi said he’s saving money for his children to be able to attend tourism school so they can work on cruise ships. To work on a cruise ship, you have to be 22 years old, know English, and have attended one year of tourism school. It’s a huge commitment for the whole family because the family needs to move to Denpasar or Ubud to attend tourism school. And then the oldest child will reach back and help pay the way of the younger children. Gus said, “This is my dream.”

I asked, “What if your child wants to be a teacher? Or an engineer? Or something else?”

He said, “Rich people can study economics, medicine, law or banking. Poor people need to get good jobs.” And according to Gus, that’s on a cruise ship.

I was quiet for a while after we talked about all of this. Taking in his words and the beauty all around us. We kept walking on our narrow path.

And then Gus stopped in front of a newly planted rice field and said, “This is my land.” He showed it to me with pride.

Then he excused himself to go fix the irrigation and adjust the water level.

Gus said he’d be out plowing his field in the afternoon as soon as our hike was done. When I asked how he plows it, he said the local farmers share a small tractor.

Two and a half hours after we started, our magnificent, thought-provoking walk was over. Gus led me back out toward the road.

On our way out, we passed this place with bagged plastic. Gus said the Balinese are working on cleaning up plastic. People can now collect it in bags in exchange for cash or rice.

On our long walk back to the hotel, we ran into lots of children riding scooters home from school. They start driving scooters as early as ten, sometimes sooner.

We passed rice drying in the sun.

These roosters were loud. They’re stored in these cages for cock fighting.

By the time we finally made it back to the hotel, I was tired, hot, and sweaty, ready for a shower and lunch, with lots of food for thought.