Dear Mom,

Today would have been your 90th birthday and it’s the day we’re going to Machu Picchu. I think it’s fitting because you were such a world traveler, always planning the next trip, always eager to regale everyone with your travel stories. But you never made it Peru. You never saw Machu Picchu, though you saw the Sphinx and the pyramids, the Mona Lisa and the Eiffel Tower. So, I’m going to keep you tucked in my heart and share my day with you. I know so much you’d love to be here.

Our day started early. Karyn’s alarm went off at 4:00 AM. Mine followed in rapid succession at 4:05. Everyone in our group gathered in the dining room of our hotel for a very early breakfast. As Michelle put it, “It was a good breakfast, but I probably won’t remember eating it.”

I chose quinoa pancakes with maple syrup, scrambled eggs and even had a cup of coffee, which I never drink except for special occasions. It was 4:00 AM after all.

After breakfast, six of the women in our group clustered in the women’s room, waiting patiently for a single stall. I wasn’t feeling very patient. “I’m going to the men’s room,” I announced. We’d all been forewarned that there was only one bathroom at the entrance of Machu Picchu and none at all inside, and we all wanted to be prepared. While we stood in the lobby waiting for everyone to gather, Karyn offered, “If anyone needs help pooping, come to me.” She was referring to the power of the yogic twist.

Brenda reminded us that we had to have our passports to get into Machu Picchu. We all double checked and then Karyn and I left our room key at the front desk. Last night at dinner, Annie, one of the most seasoned travelers of a seasoned group of travelers told us, “When you stay in a tourist town, ALWAYS leave your room key at the desk. Pickpockets will target your room key and then go in and clean you out. If you leave your key at the desk, it’s the hotel’s responsibility if you get robbed.” I filed away that piece of sound advice and many of us took it today.

I also learned, “If you have to put on both sunscreen and insect repellent, put the sunscreen on first, next to your skin, and the bug juice on top, closer to the bugs.”

The forecast was for 75 degrees, but when we headed outside to walk to the bus stop at 5;00 AM to wait for the bus for the final leg of our journey up to Machu Picchu, it was still cool outside. The early morning light was grey. We walked uphill to find the end of the line, which was already very, very, very long. There was a lot of excited talk in dozens of languages I couldn’t begin to recognize. Dozens of varieties of hiking boots and hiking sneakers, every kind of expensive high-tech gear. Every color of hat. Contracted hiking poles, all with rubber tips, sticking out from thousands of backpacks.

We kept walking up the hill. The line seemed to be endless. When I caught up with our crew, someone said, “It’s quite a queue!”

Brenda responded, “It usually goes pretty fast. We’ll probably be in line for an hour.”

As we slowly walked, we passed one souvenir vendor after another, selling water, postcards, super thin colored ponchos, fruit, candy bars, coffee, jewelry, incense, colorful woven water bottle holders, hats with Peru and Machu Picchu stamped across the front, sticky buns, a blackboard with the words MENU TURISTICO and JUGOS (juices): papaya, pina, platano con leche, mango, naranja, manzana and especial.

The Urubamba River ran in the wash below us. The streets were mobbed with people, lots of excited chatter and picture taking. As I looked at the members of our group, bonding and talking happily, no one sick, everyone able to fully participate in our Machu Picchu day, I felt a shot of pure joy. All of these people had come together because of something I had created. As if reading my mind, Meredith, a long-time student of mine, turned to me and said, “I’ve met the best people through you.” That’s what I love best: creating community. I took in each of the eighteen people who’d come on this trip in turn, really taking them in. I felt a rush of love for each one. I knew their stories. I’d sat with each of them. I’d laughed with each of them. Many of us had cried together in writing group. We’d held witness for each other and writing class—and daily yoga—had created a powerful bond. And now we were going to share this special adventure together. For many of them, this trip to Machu Picchu was one of the main attractions of this trip.

I, however, didn’t have any particular expectations. Last December, when Karyn and I went to visit our daughter Eliza in Beirut, we’d traveled to the desert in Jordan and I’d been blown away by Petra. But a few years back, when we took a group to Southeast Asia, I’d been unimpressed by Siem Riep in Cambodia. What I felt more than anything in Cambodia was the history of trauma that permeated the place.

The top world heritage sites are often mobbed with tourists and hawkers and sometimes beggars. Often you can barely walk because of the crowds and are constantly dodging people posing for themselves with selfie sticks. I didn’t know what to expect of Machu Picchu, but I wasn’t holding it up as the highlight of my time in Peru.

So, I really didn’t know what to expect of Machu Picchu.

A woman in a uniform came up the hill, checking for everyone’s bus ticket and passport, efficiently stamping them as she moved through the line.

Across from us, on the wall on the other side of the river, there was a beautiful carving. “It’s not an ancient carving,” Lourdes, one of our guides for the day told us, “They’re making them right now.”

We walked under a bridge covered with small padlocks locked up and down the mesh walls, each one a declaration of love. Mom, you were the first one to tell me about this tradition after your first trip to France more than 40 years ago, after Dad’s stinging abandonment. It was when Dad left, when you were 43 and I was 14, that you got your first passport and started to travel. You never stopped until age stopped.

I didn’t get my first passport until after I was 40, and just like you, I don’t want to stop traveling.

As it turned out, Brenda was right. We boarded the bus an hour after we got in line. It barreled along a windy rock studded dirt road that ran along the river, the foliage more tropical than it had been, more like jungle.

Pretty soon we were speeding around switchbacks at a speed I never would have attempted. Other buses roared past us downhill in the other direction, back to town. We were definitely climbing, and the jungle intensified on either side. The road changed to stone, then back to dirt again. Fog dressed the tops of the sharp white granite peaks that surrounded us broke through the vine-covered foliage. Every time the bus made another hairpin turn, there was a new vista. Even though I hadn’t been excited before, a small candle of excitement caught fire inside me.

And then we were there. We piled off the bus and got in the queue for the bathroom—2 soles per person—about 75 cents. The woman who collected the toilet money sat in a cute little wooden booth like a ticket taker at the movies. We even got a receipt.

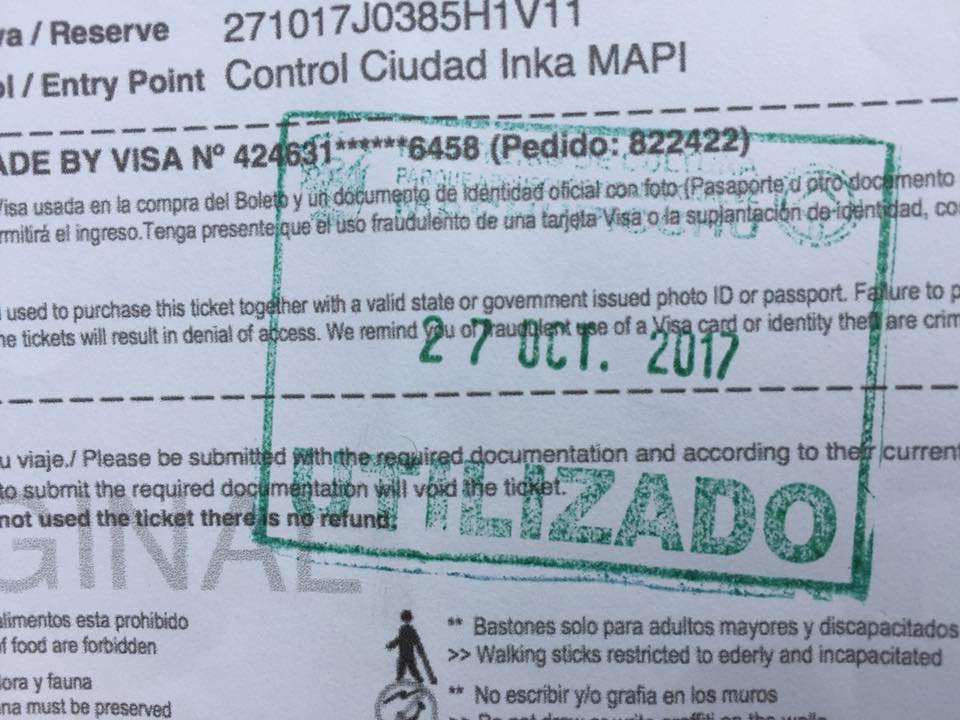

Bathroom business attended to, we got in line to enter the gates of Machu Picchu. The ticket takes looked at my passport and stamped my ticket with your birthday, October 27th.

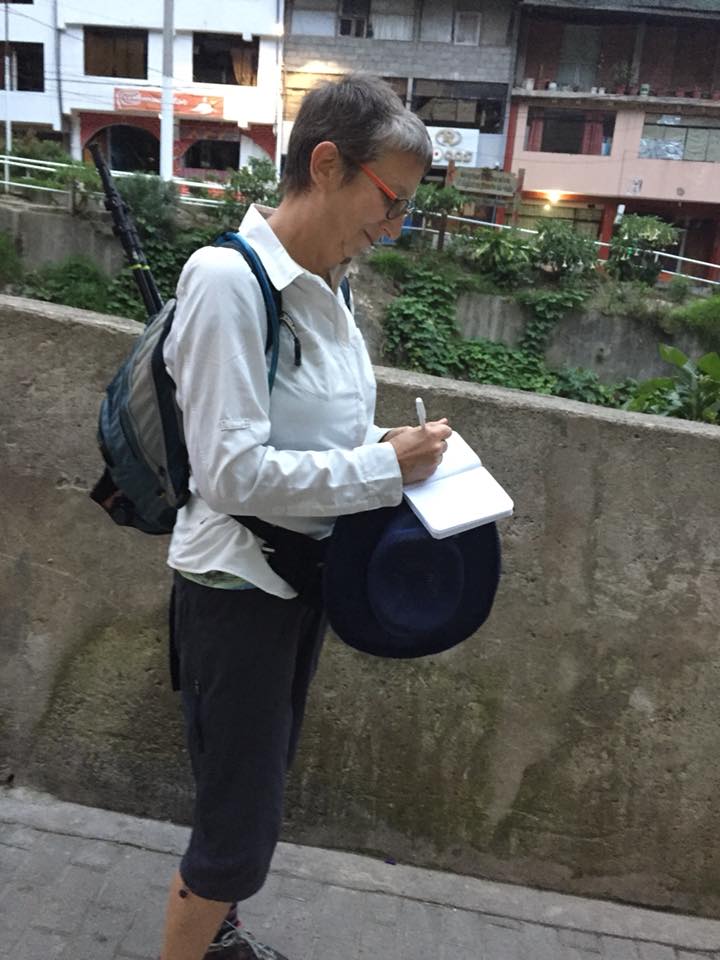

And then we started to climb up a steep, curving flight of stone steps. I panted up those steps. They were steep and they went on for quite a while. Every once in a while, I’d stop to take notes in my little notebook. Glen looked down at me from above and called out, “Laura, you can’t write and climb at the same time.”

At the first major viewpoint of Machu Picchu, all of us gathered together and looked at out at what might have been a view. But all we could see was a thick wall of mist. Kendra said, “We could have slept in and taken a later bus.”

Glen said, “The fog bank is from all our heavy breathing on the way up.”

Our guide, Lourdes, said, “Everyone who was born in the month August, needs to stand near the edge and blow the fog away.” That was Karyn. She stood at the edge doing ujjayi breath, a special kind of yogic breathing, and moments later, like magic, the mist began to lift from left to right. The first picture below is what we saw.

Gradually what had been obscured became clearer and clearer. Then the mist over the mountains started to clear. Moments later, the view as crystal clear. Brenda smiled one of her warm, encouraging smiles and said, “It’s like it’s unveiling itself for you.”

Moments later, it was all ensconced in mist again. People sat everywhere, patiently, waiting for it to lift again. As we waited, Celinda, one of our fantastic guides gave us a fascinating briefing. “You can understand why this site was hidden for centuries. It’s on top of a mountain. It’s covered by clouds most of the time and trees grew over most of it.

“It was in 1911 that Hiram Bingham from Yale became the first westerner to “discover” Machu Picchu. He was on an expedition to Peru, trying to make a name for himself as a famous explorer. He discovered Machu Picchu on July 24, 1911. It was overgrown and hard to see and two families were living here. The farmers knew about it. The people living here knew about it, but Hiram Bingham is the man who gave the world Machu Picchu.”

We leaned again the wall, seated on our ponchos, many of us quickly adding a second of third layer in the chill of the fog. Celinda sat on the ground before us, her arms dancing as she spoke. “There are different theories about why Machu Picchu was built here. The first is religious; Machu Picchu is surround by three important mountains, all aligned with each other, and many believe this place was built for the apus.

“The second reason is functional. It’s more humid here and crops grow well. The families living here were growing potatoes and corn. Machu Picchu is called the Gateway to the Amazon and the Incas wanted to conquer the Amazon because coca leaves were grown there. Also, the top of the mountain was safe from enemies and from the flooding of the Urubamba River.

“And the third reason is the water supply. There was plenty of water, two springs and a large reservoir.”

As Celinda spoke, the mist began to clear again and we could see the view. More and more people were pouring in, but as we sat against the stone wall listening, we felt like were in our own private world. Down the hill from us, a group of eight meditators sat silently, eyes closed, back straight. It was as if we were each having our experience of Machu Picchu.

Five minutes later, all was shrouded in mist again. “The mist,” Celinda explained, “isn’t clouds or fog. It’s steam from the Amazon.”

Glen, who always has good questions, asked, “How did the stones get here?”

Celinda said, “The stones were already here. The real question is, ‘How did the soil get here?’ The Incas transported by hand tons of soil from the Sacred Valley—rich topsoil to grow crops, clay to make stucco and sandy river soil to fit between the boulders and to help level the land.”

We all tried to wrap our minds around the kind of labor that required. What we learned was that the labor that built Machu Picchu was extracted in taxes by the Incan kings. Instead of collecting money, labor was required on an annual basis, and much of it went to constructing Machu Picchu.

When Machu Picchu was completed, smallpox came and 90% of the population died. It was biological warfare. If that hadn’t happened, the Incan’s could have defended themselves from the Spanish forever. How could anyone have waged a successful a successful siege on this place if the population has been decimated?

It was time to get up and start walking again. As we adjusted our layers and picked up our walking sticks, the sound of train rose up from the valley.

Mom, I tried to imagine you here—being here with you—sharing this moment with you and I couldn’t. We never shared moments like this. Once when I was a teenager, you offered to take me to Israel and I scoffed at you. We never traveled together after that; we were never comfortable travel companions together in that way. But I feel you here with me today.

After another second set of steep steps, we turned onto part of the original Inca trail, a gradual incline on a dirt and stone. Coming down in the opposite direction were people hiking in after four days on the Inca Trail, about to get their first glimpse of Machu Picchu. One woman said dismissively as she passed us, “I smell perfume.”

Someone from our group called out, “It’s bug spray.”

Someone else said, “We smell you, too.”

And then we entered the door to the city. Mom, I wish you could have been there. Happy birthday.

(If you readers would like to get your tour of our day and of the Machu Picchu, move on to the pictures, but be sure to keep reading the captions. The story continues there.)

The line.

Here I am again, taking notes in my notebook.

The new carving alongside the river.

Aren’t these the cutest?

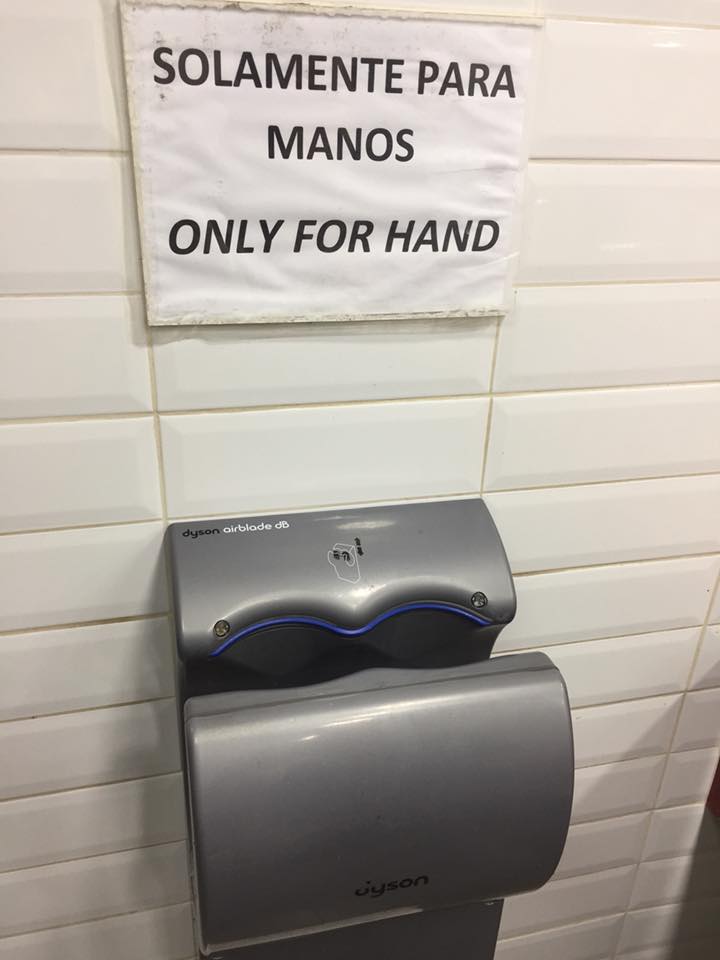

Here’s the hand dryer in Machu Picchu’s only bathroom. I love air blades. It’s fun sliding my wet hands up and down in the blast of hot air, but what the hell did something try to put in there that caused them to put up this sign?

The bathroom ticket taker booth.

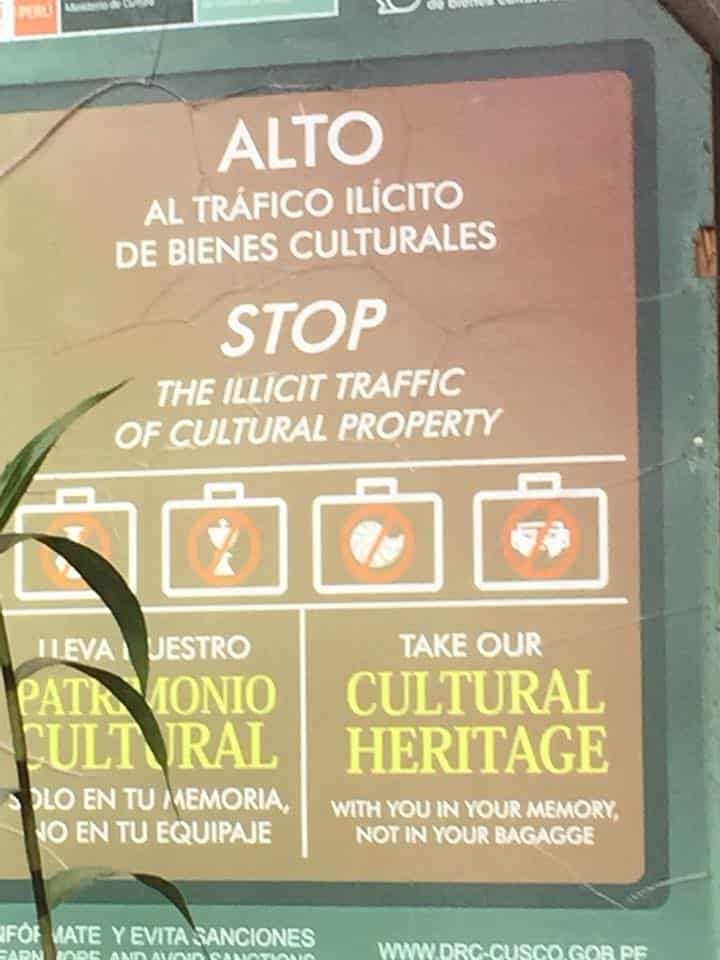

The rules.

My morning pass, stamped with my mother’s birthday. She would have been 90 years old today.

Our first glimpse as the mist cleared.

Ten minutes later.

Then the fog over the mountains started to clear. Moments later, the view was crystal clear.

The Inca trail.

Waiting for the mist to dissipate.

Tamara, Brook, Juliana and Doug.

Alaina looking spiffy.

Celinda was a fantastic guide.

The view got clearer and clearer the longer Celinda spoke.

The city.

Terraces.

The view from inside the city looking out.

See how new stones are placed around the original rocks?

This is Karyn doing “yoga on the go.” She’s explaining how to realign the knees after walking down the lots of step.

This is me and my notebook in the ancient city.

The Incas built three kinds of terraces: terraces to grow crops, terraces that were more like retaining walls to prevent erosion, and decorative terraces to add beauty to the city.

There is no way you can imagine the majesty and the mind-blowing vistas of Machu Picchu from looking at a photograph on the website or in a tour book. I could have taken hundreds of pictures and only caught a fraction of what I saw.

Look who just happened to be wandering around!

And this one is just for our granddaughter, Ellie—her Grandma Karyn and the llama, because Ellie loves the book, Is Your Mama a Llama?

Gabled roofs.

Doorway.

This is the sun temple. It’s built of white granite and if it still had its roof it would be white. Now, exposed to the elements, it’s grey. On the morning of the winter solstice, the sun rises through the largest window. On the morning of the summer solstice, the sun rises through a different window. This was just one of many important temples. The Incas were amazing!

This is the window the sun came through during winter solstice, from the outside.

From the top, Machu Picchu looks small, but when you get inside it, you realize how big it is. It really was a city.

This is stonework from the back of the astronomer’s house. Hiram Bingham called it, “the most beautiful wall in South America.”

I expected Machu Picchu to be like this—jammed with thousands of tourists with selfie sticks, and it was, near the entrances and exits, but most of the time we were on the site, it felt sacred and we often were alone or only with a sparse crowd.

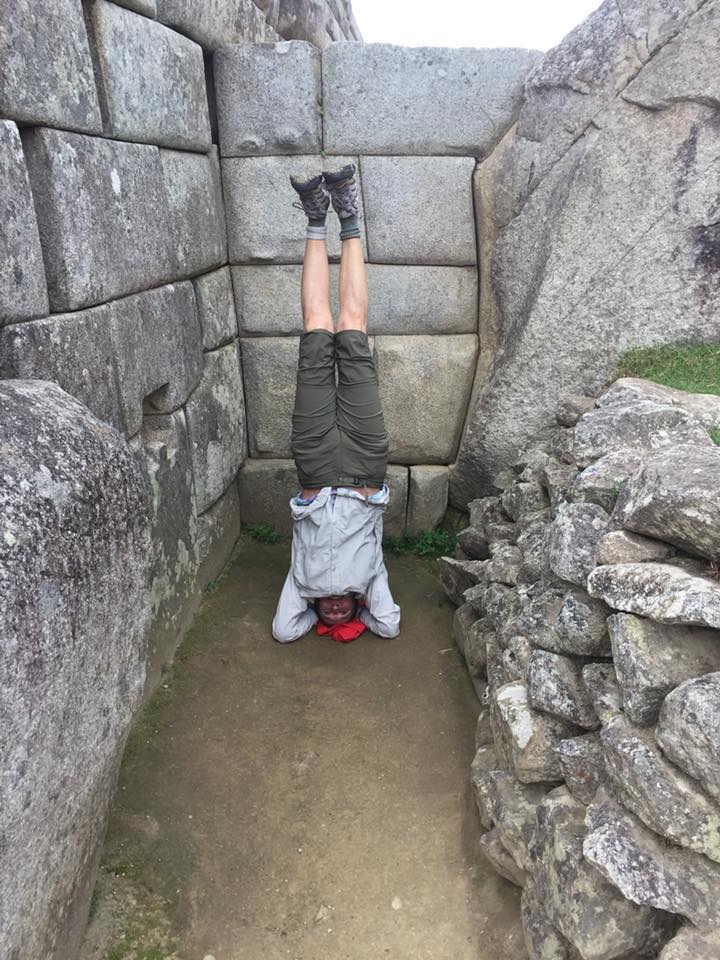

I joked with Karyn. I told her she should create a calendar called, “Headstands Around the World.”

Sundial.

All around us, everywhere we turned was another vista of steep green mountains jutting up all around us. It was almost too much to take in. My expectations—which I hadn’t had—had been blown out of the water. But we were hungry, we all had to pee and my knees needed a break. We passed this doorway on our way down, where we waited for a sumptuous lunch. You can find out what we did after lunch, in Machu Picchu: The Sun Gate.