I was up this morning at 3:30 AM with a headache. I’ve had a headache for some part of every day I’ve been here and the day we went up to Cusco to pick up our students, at 11,000 feet, I felt like my head was in a vise the whole day.

As soon as we came back to Sach’a Munay and 9000 feet, that intense pressure lessened, but I’ve still had a headache everyday for at least part of the day. I’m sure the advil I’ve been taking on a daily basis can’t be good for my gut, but it helps. I would say my discomfort has been at a 4. I’ve been able to do everything—teach, schmooze, take part in a sacred ceremony, even hike, but that pressure in my head is always lurking.

Each day I think, “Oh, tomorrow I’ll adjust.” But I’ve already been here for almost a week and I seem to be one of those people whose body just doesn’t like high altitude. I’ve been drinking cocoa tea every morning and taking chlorophyll, but I haven’t resorted to the big guns, the diamox my travel doctor, Arthur Dover, prescribed. It’s designed for mountain climbers, for people suddenly ascending beyond 10,000 feet. Most people told me I might have a couple of days of discomfort and it would pass, but it hasn’t passed.

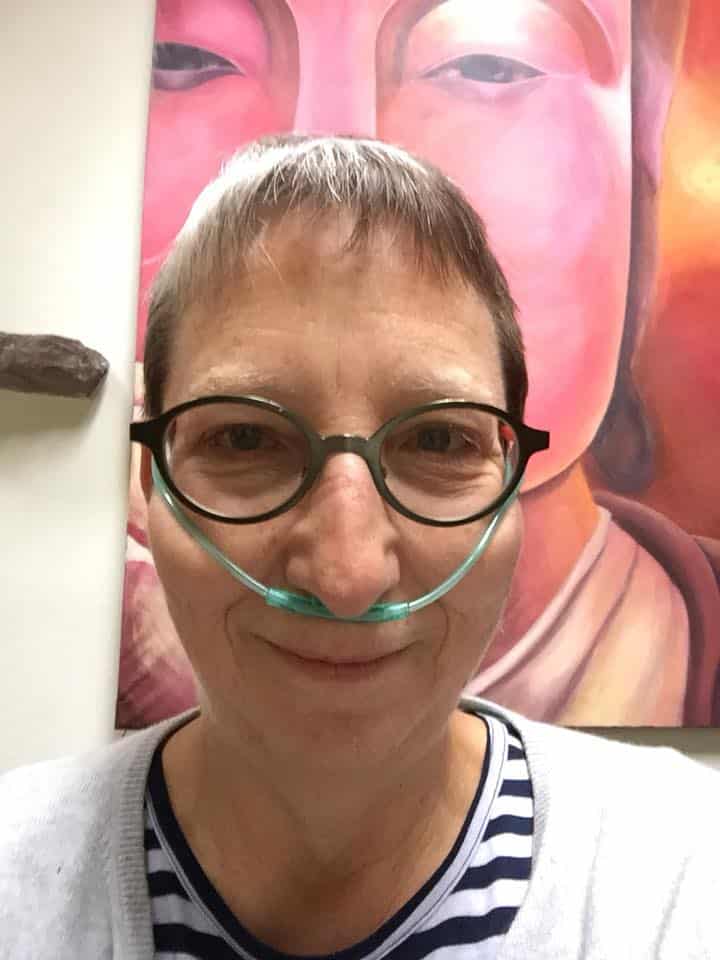

This morning, Brenda, our guide, with whom Karyn and I are sharing digs, told me that there was oxygen on the premises, and that I might want to try it. Since I’d been up since 5:30 and yoga wasn’t until 7:00, and my class for the day was already planned, I figured why not. So I went to borrow the oxygen tank and as soon as I saw the green canister and the plastic tubing dangling from the top and those nasal canulas, I was brought right back to the last year of my father’s life, seventeen years ago, when he’d sit at his Goodwill table in his space at Project Artaud in San Francisco, head in his hands, too tired to get up or eat a bite of soup, congestive heart failure zapping his strength, always with that oxygen following him around. Many of my last images of him are of his slumped body and those plastic tubes up his nose. And here I was, hefting this green oxygen tank with my sturdy strong body, that yes, is getting older, headed for my room to slip the canula into my nose, the tubes around the back of my head.

And so here I sit, looking out at the sharp mountain peaks outside my window, flowers surrounding this suite, to my right another amazing stone wall with the rocks never laid in symmetrically, but wedged in randomly to provide stability, beside me, my Writer’s Journey bag with my notes for our morning meeting and my teaching notes. My backpack is already packing for our afternoon excursion with a local guide to the beautiful Incan agricultural terraces of Moray, and the nearby salt mines of Maras: my down coat, folded into its own pocket, my green Patagonia raincoat, folding into its own pocket, sunscreen, a sun hat, lip balm, a liter of water, some soles—the local currency—and my passport, which is required for entry into the major archeological sites. I’m very much looking forward to the day—to my students, to our second class together, to our adventure this afternoon, to another yummy breakfast and in just a few minutes, to Karyn’s yoga class. But here I sit, remembering my father, hoping this little jolt of oxygen will eliminate the traveler’s discomfort that has been dogging me each day.

Would I come back to Peru and this altitude? Absolutely. Karyn and I are already dreaming about our next trip. Travel brings discomforts and I think they increase as we get older, but the benefits—they far surpass them.