Judy Slattum, tour leader, Danu Tours.

Surya Made, Danu Tours, Judy’s husband and partner in their great boutique tour company.

Yesterday we picked up our travelers from all over the world: Australia, Mexico, Canada, California, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. Judy and Surya went to meet the first batch and our Vietnamese guide, Quynh, picked me up to so we could go together to meet the second wave. When we walked out of our hotel, he ushered me into an amazing bus. This was going to be a lot different than hoofing it on the streets of Hanoi on foot!

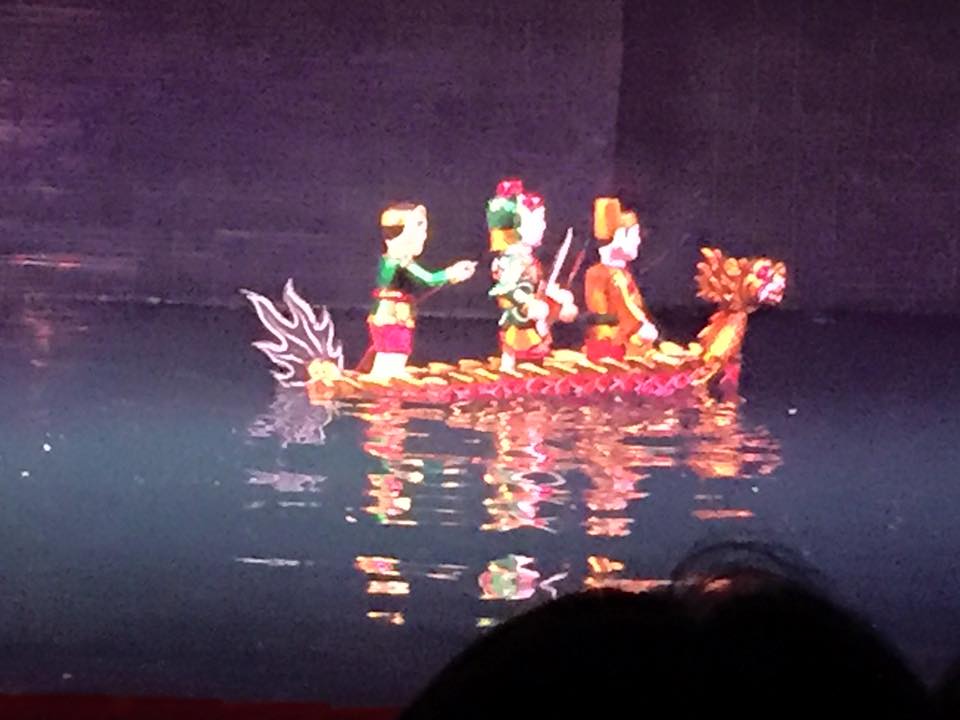

After the typical travelers’ delays, we rounded everyone up and got them back to our hotel. Then our job was to keep them awake for the next 7 or 8 hours until it was time for a proper Hanoi bedtime. This meant only letting them drop their things in their rooms and NOT LAYING DOWN, and immediately getting everyone to go out again. We piled everyone onto our bus–a very different view of Hanoi than feet on the street–and went to a water puppet show, a must-do for every tourist in Hanoi. I can see why. It was enchanting. The puppets, which included all kinds of animals, fish, dragons and people, were “played” in a lake of water in front of us. The show was accompanied by music on instruments I’d never heard before in a lovely lyrical companion to the delight of the puppets. This art form has been practiced since the 10th century in Vietnam.

After the show, we had a lesson by Quynh on street crossing: “You’ll want to go fast, but what you should really do is slow down. Be like a pebble in the middle of the stream.”

We walked down the street, most people’s first taste of urban Hanoi, and I could see everyone’s eyes go wide. We got into individual pedicabs, where the bicyclist is in the back and the passenger is in the front. We were pedaled around Old Town and then hopped off and explored on foot.

I starting conversations with our new arrivals: saying hello to the people I already knew (a little less than half the group) and meeting and greeting the ones I didn’t. Reuniting with my partner, Karyn, who will be teaching yoga on this trip, and our daughter, Eliza. Everyone had been traveling for a VERY long time. They were tired and ready for bed, like NOW, but we kept them moving. We ended up at a restaurant for a many-course, very good meal, and finally, got everyone back to our hotel by 9 where they all crashed.

It’s really the best way to make the time change when traveling to Asia.

Now that our official tour has begun, I noticed how much I enjoyed having a guide explain things to us. There were so many things I’d witnessed over the past few days that I didn’t understand. And now I had a way to make sense of what I’d seen. Like why people everywhere cook and eat on the street. It’s because in Old Town, families of five or more live in single 200-square-foot rooms. No wonder they eat and cook and live outside–there’s no room to prepare food inside.

Quynh taught us that Vietnamese words are all one syllable. It’s not Hanoi. It’s Ha Noi. And that’s not remotely an accurate depiction of the name of the Vietnamese capitol because my keyboard doesn’t allow me to type in all the accent sounds that let you know how a word is to be pronounced. It’s all in those marks which let you know how to “tone” the word. For instance, Quynh told us, the word “ma” can mean mother, ghost, tomb, horse, young rice or “so this or so that,” depending on the tone given to the word. Vietnamese is a toning language, like Chinese, only it has 6 tones and Chinese, only 4.

Quynh: Our Extraordinary Local Guide

I found that fascinating and was happy our travelers had arrived. Still, it was an adjustment to go from being on my own with Joanie, going where we wanted, when we wanted, and changing plans at a moment’s notice, to traveling with a large group I was responsible for. With a printed (but flexible) itinerary.

So this morning, before our scheduled day began, Eliza and I slipped out of the hotel at 6:30 AM on a mission to walk over to Ho Chi Minh’s mausoleum to view the glass sarcophagus that holds his pale, embalmed body. Uncle Ho (as he is loving referred to by the Vietnamese) is open for viewing every morning from 8-noon, except for two months each fall when his embalmed body is shipped to Russia for maintenance.

The mausoleum was built in Ba Dinh Square on the site where Ho Chi Minh read the Declaration of Independence on September 2, 1945, establishing the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. It’s a sacred site for the Vietnamese who consider Uncle Ho their George Washington, the father of their country.

Eliza and I have a history of being interested in sites connected to the dead while traveling together. One of my favorite outings with her in France, back when she was 13, was walking through the catacombs under the streets of Paris, wandering past millions and millions of stacked skulls and bones. So when this opportunity came up to see the embalmed body of a beloved Communist leader, I knew it was the kind of outing we’d both say yes to.

On the way to Ba Dinh Square, we were delighted by what we passed along the way: dozens of Vietnamese out in the early morning on the sidewalks and in the parks, exercising. During our twenty-minute walk, we passed a ballroom dance class in a park complete with twirling couples, badminton being played on the sidewalk with and without nets, people doing Zumba, and 20 middle-aged women sharing a tai chi class at the end of a dead end street. It was delightful to see so many people out moving their bodies as the way they start their day. I loved that it was free and public and such an accepted part of daily life.

When Eliza and I reached the mausoleum and got in line, there was another line parallel to us, and for the whole 50 minutes we waited for the viewing to begin, a middle-aged Vietnamese woman stood, with her back to us, doing a cheerful peppy salsa while standing in place, swinging her hips the entire time. She was wearing a red fleece jacket, a shiny blue backpack, a pair of jeans with a Hello Kitty patch on the pocket and a pair of tiger print, high-heeled sneakers with huge tan heels and bright orange puffy trim. I really wanted to take a video of her so I could show it to you, but cameras are not allowed in the mausoleum (nor are hats, backpacks, laughter or smiles–this is a very somber occasion). So I didn’t dare pull out my I-phone to catch a couple of minutes of Salsa Woman in action. She really made us smile.

There were no signs directing us where to stand, no one who spoke English to tell us what to do, so we stood where we thought we should, but we were puzzled; we’d been told that there was usually a 45-minute wait to get a viewing of Uncle Ho’s body, but there were only six westerners standing in our line. The Vietnamese in the line next to us (include Salsa Woman) left to join what looked like a tour.

Finally at 8 AM, while Eliza and I were still the first in line, a guard motioned us to pass through a metal detector. Once we got through it, we saw another huge line moving in front of us, a thousand people coming from another direction entirely, passing us by on their way to the front door of the mausoleum. We watched them go by for a long time until finally we were allowed to merge into their line. So much for the benefits of arriving early.

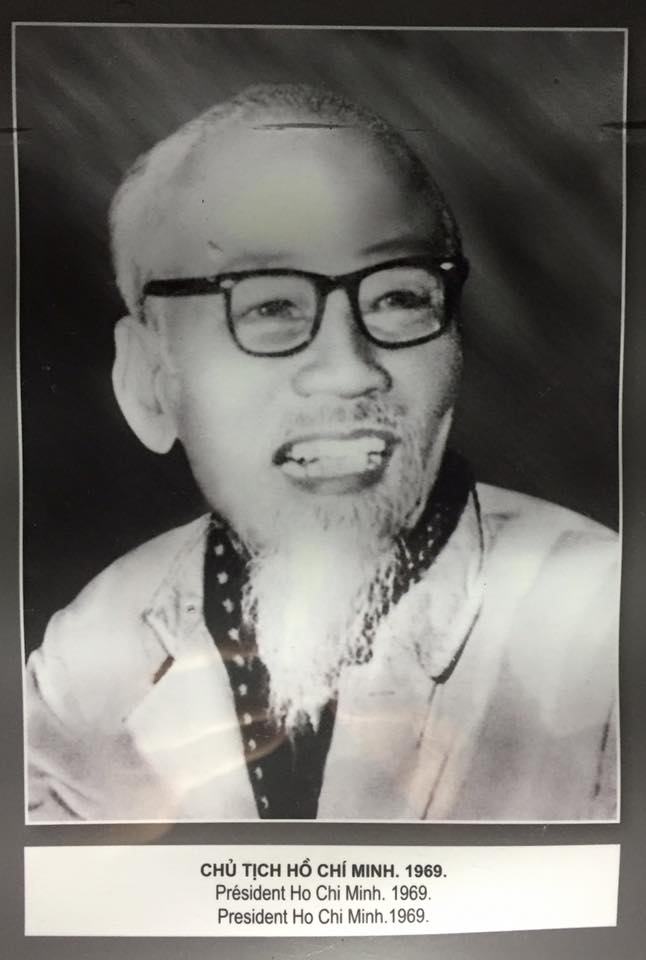

We entered the front door of the mausoleum past guards in impeccable white uniforms with gold and red trim, and were careful not to laugh or smile or behave disrespectfully in any way. We walked around a bend, up a flight of steps, and then suddenly there he was. We walked slowly in a horseshoe around the sarcophagus. Uncle Ho was lit up, his body lying on a slight incline. He looked more real than a wax museum figure, and he had the goatee I remembered from all the anti-Communist propaganda pictures of him I saw during the Vietnam War.

The whole ritual of the viewing reminded me of a time forty years ago when I was a devotee of young Guru Maharaj ji and once or twice a year, we’d get to go to see him for darshan, which meant being in his physical presence and getting to kiss his “lotus feet.” We’d wait in line for hours and hours until the moment when we would get to file past him and then quickly bow down to kiss his white sock-covered feet. There were always guards there, waiting to pull us up and hurry us along in line. We had maybe two seconds at Guru Maharaj ji’s feet and if we were truly blessed by grace and very lucky, he’d glance down at us. After our two seconds of darshan, we’d be crying or blissed out. Sometimes, people would faint or would have to go to the darshan recovery tent, they’d be so overwhelmed with blissful emotion.

I’m sure that for many Vietnamese visiting this site, seeing Uncle Ho’s body is a very big moment–full of pride and emotion about the man who led their people to finally overthrow the cloak of colonialism and attain independence.

Eliza and I walked all the way around the horseshoe, staring at Uncle Ho’s lit-up body, and moments later, we were outside. “That was really cool,” she said.

“Yeah,” I said, really glad to have made the early morning effort. Glad to have seen it with her.

On our way back the hotel, we decided to try Quynh’s street crossing advice. We picked a busy street and looked at each other and then just slowly walked across. It felt like we were parting the Red Sea. There was some kind of beautiful symmetry to the bodies and vehicles moving past each other in space. Kind of like those couples we’d seen waltzing in the park at 6:45 in the morning. We high-fived each other when we safely reached the other shore. We had done it like locals.

Moments later, we passed the street where the women had been doing tai chi an hour earlier. Now they were all eating breakfast together on the grass right beside the street, laughing and talking together. What a beautiful way to start the day!

Later, after we’d had breakfast and gone over our plans for the day, our group spent a couple of hours at the museum commemorating Uncle Ho’s life, and it gave me a much greater appreciation for the man who had always been demonized in the U.S. coverage of the Vietnam War I had heard every morning as I got ready for elementary school, as I ate my toasted cinnamon-apple pop tarts. We were in the War because we had to protect ourselves from Ho Chi Minh and the Red Menace–the Communist threat spreading from Russia that was going to take over the world if we didn’t go to war in Vietnam. That’s what Nixon said to justify the war. But in our family, we hated Nixon. We hated the War.

Fifty years later, I was happy to get a new picture of the brilliant, charismatic humanitarian leader who brought the Vietnamese people independence, a man honored by the General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in November of 1967 with the following words:

“President Ho Chi Minh, an outstanding symbol of national affirmation, devoted his whole life to the national liberation of the Vietnamese people, contributing to the common struggle of peoples for peace, national independence, democracy and social progress…The important and many-sided contribution of President Ho Chi Minh in the fields of cultural tradition of the Vietnamese people which stretches back several thousand years, and that his ideals embody the aspirations of peoples in the affirmation of their cultural identity and the promotion of mutual understanding.”

P.S. Today is the day Eli is supposed to catch his flight out of the Midwest to join us. Keep your fingers crossed for us!

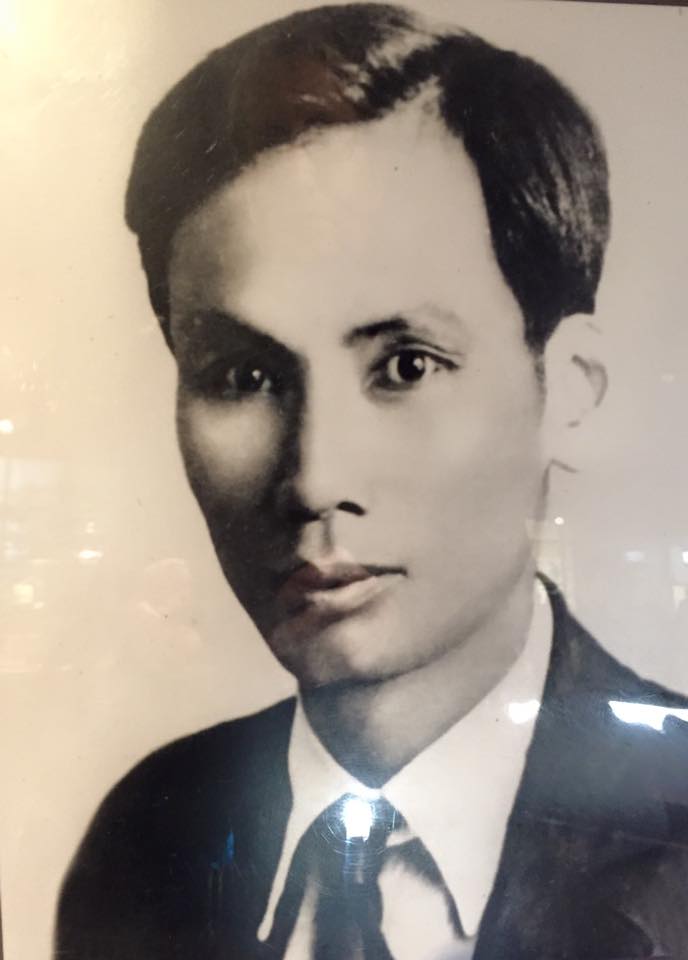

A young Ho Chi Minh.