Our home for the next six days, Luang Prabang, the City of the Holy Buddha, is currently celebrating its 20th year as a UNESCO Heritage Site, something that is both a positive and a negative for the locals. It is a positive because of the tourist dollars it brings into the area and a negative because the UNESCO designation includes rigid rules about the preservation of old buildings and the existing look of the town.

And, of course, there always the downside to tourism and its impact on local culture.

After a lovely breakfast in our hotel (I tried rice porridge with onions and mushrooms – one of the traditional Lao breakfasts), we met at 8:30 for our walking tour of the city. The mornings and evenings here are cool, but the afternoons get to be 80 degrees, so we were instructed to dress in layers and wear good walking shoes.

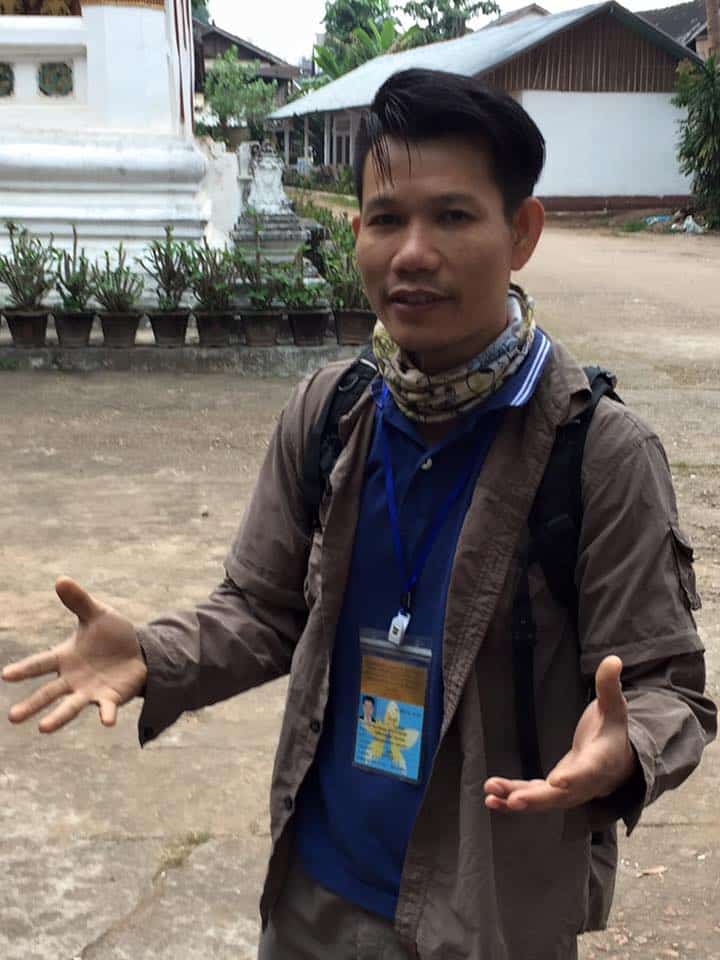

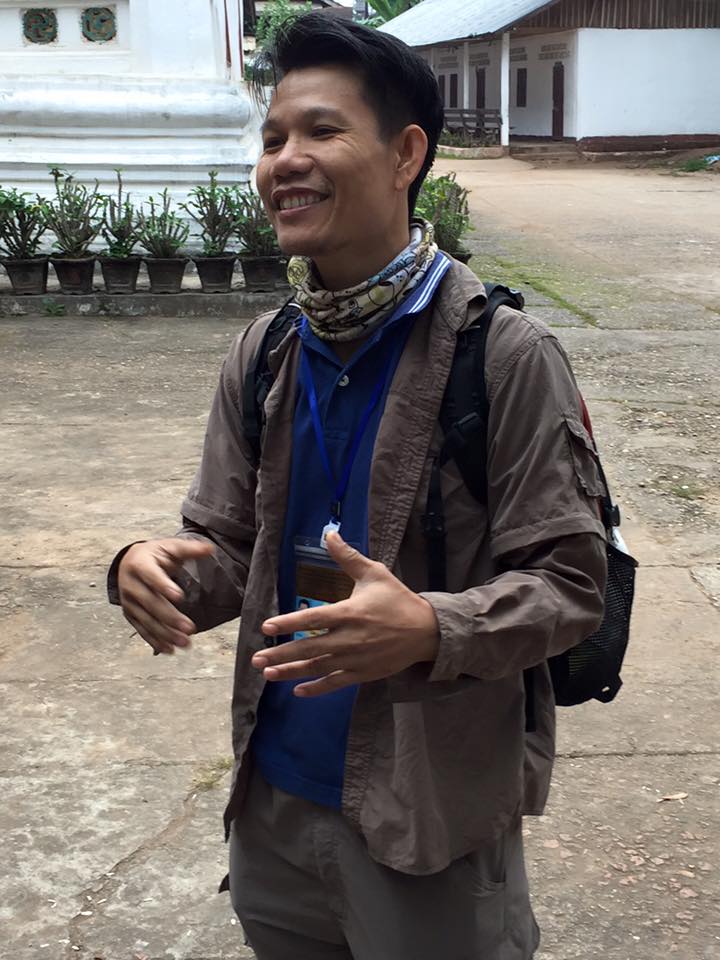

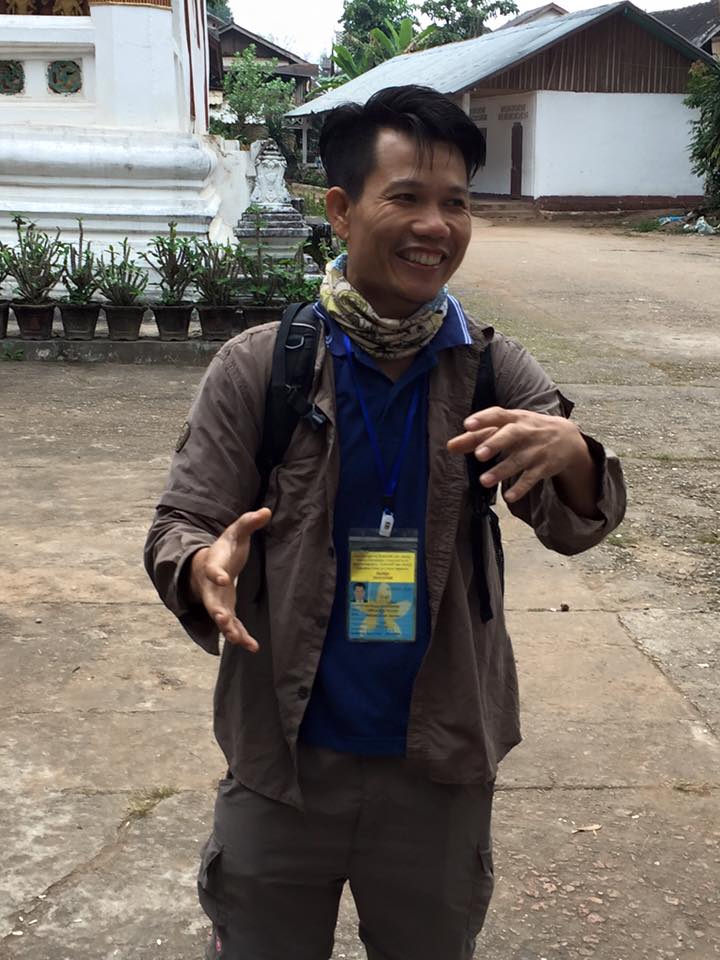

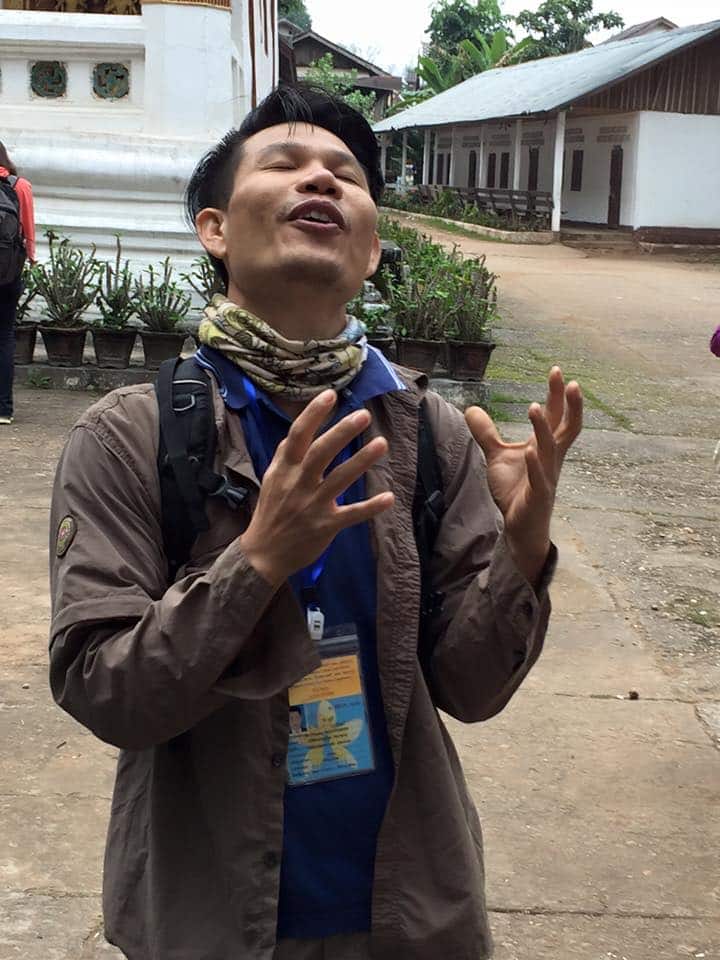

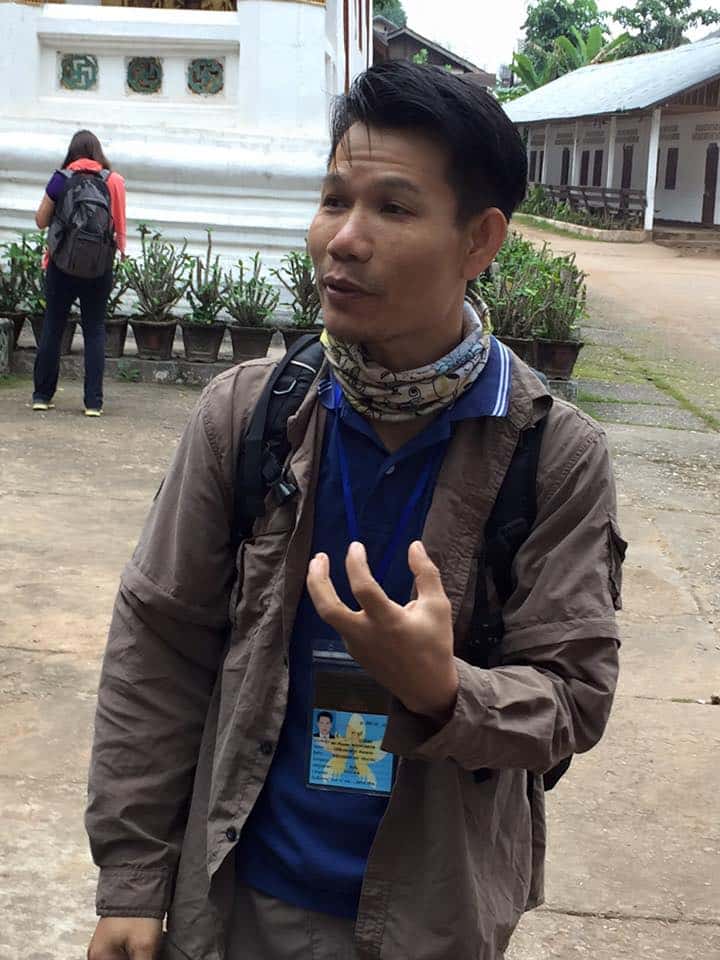

Our local guide, Tui (pronounced two-ee) took some time to introduce himself before we headed out and he immediately had us all in his thrall. We were entranced by his accessibility, his warmth, his sincerity and his amazing smile. Every time Tui smiled, his whole face cracked open with joy. Tui’s English was wonderful. “You are my family right now,” he told us. Then he taught us our first two terms in Lao:

Hello: Sa bai dee

Thank you: Kup jai

Our first stop of the day was to change dollars into kip; our second, to pick up insect repellent for those who needed it and hadn’t brought it along. With those essentials taken care of, we hiked up to Wat That Chomsi, the Buddhist Stupa located at the top of Mount Phousi in the center of town. Reaching the top, and the 360 degree views of the Mekong River and the entire town, requires climbing 238 steps, one flight at a time. Many of these steps are accompanied on either side by ornate carved dragon railings. The dragons are called naga and are considered protectors from bad spirits.

Check out these naga (the rest of the post is woven among the rest of the photos…so keep scrolling and turn your images on)

I knew that Eli in particular would love these dragons. He’d been obsessed with them as a kid. There was one place along the way where the dragon statue had seven heads. I was surprised, but Eli told me in an authoritative voice, “Of course the naga has seven heads.” When I gave him a quizzical look he said, “The Encyclopedia of Things That Never Were was my go-to book from age 8-14.” I remembered that giant hardcover book: full of pictures and stories of every mystical creature ever written about, regaled in myth, story or song.

On our way up the hill, we passed tamarind trees, people creating food offerings for the monks, small shrines and a number of temples.

Halfway up the hill was the Wat Tham Phousi Shrine: a huge big–bellied golden Buddha and a second Buddha lying on his side.

Tui told us, “We don’t have bling bling temples in Laos,” but I thought this temple was pretty damn fancy.

On one of our rest stops on the way up, we had a long conversation with Tui about education in Laos. Although school is free and now compulsory at age 6, families have to pay for government uniforms and books, and also pay a school fee of $15-20 a year. And it gets more expensive at the high school level; high school kids need more than one uniform and more than one pair of sandals. When families are well-off, this is not a hardship, but for poor families with 6 or 8 children, this makes school unaffordable and it is the girls who are pulled out of school first; they can marry as early as 15, and the son-in-laws they bring into the family are seen as an asset – one more set of hands to work on the family farm.

Tui told us that families in town are having less children – two or three – but in the remote areas, among the hill tribes, birth control is nonexistent and large families – producing more kids to work the farm – is still the norm.

We had a lot more questions for Tui, (“Was your marriage arranged?” “No, I chose”), but he told us it was time to keep climbing toward the stupa.

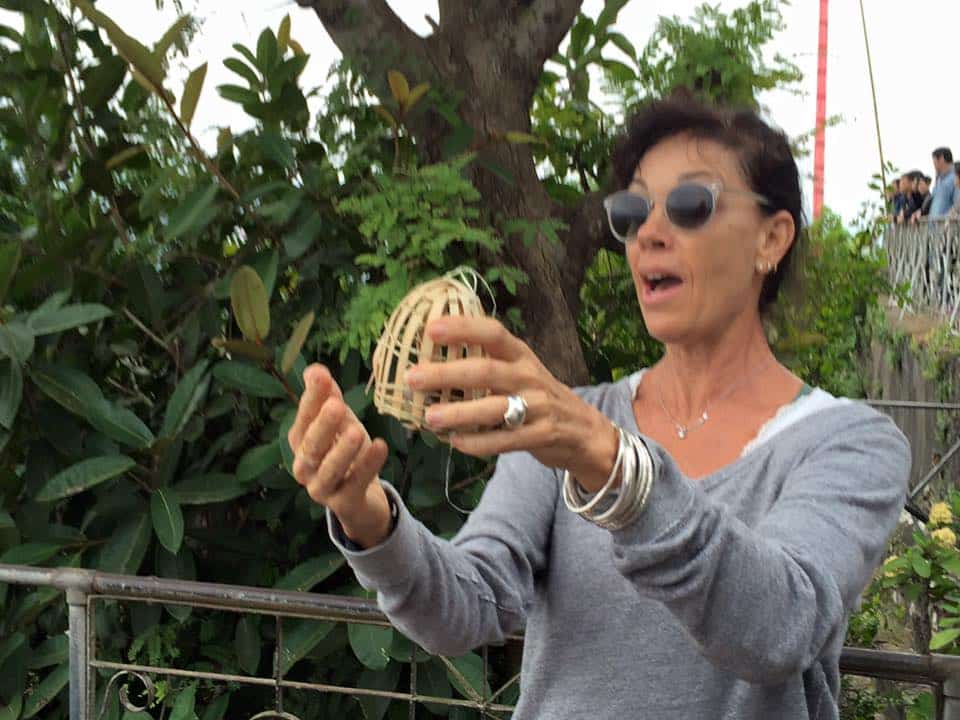

As we got nearer the top, we began passing little concession booths along the side of the trail, run by women selling incense, clusters of marigolds and little wicker cages, each of which contained two small, fluttering birds. The idea was to take these little birds up to the top of the temple and release them along with them our stresses and worries. The little birds are released and captured anew every day, put back into their little bamboo cages, then sold and then released at the top, only to be recaptured the following day. Tui said the Laotians call the birds nokagip and he didn’t know the English translation, but they looked like tiny sparrows.

Releasing birds, releasing worries:

There was a trash bin for throwing out the used cages, but since nothing in this country is wasted, moments later, a young woman came by to collect the used cages with torn out sides so they could be repaired and recycled the following day.

At the top, a group of us clustered around Surya who was talking about the American War and the toll it had taken on Laos. When American pilots were carpet bombing Vietnam, he told us, they’d fly over northern Laos at the end of their bombing runs and dump all their unexploded bombs over the Laotian countryside to “lighten their load.” There were intentional bombings of Laos as well.

Tui said his father traveled around the countryside in his work as a teacher and that he saw the destruction caused by American bombs in every single village. But Tui insisted that the Laotians have forgiven us. “The new generation doesn’t hold it against the Americans,” he told us. “We try to forgive and think ahead, not think back. Not all Americans were for the war.”

As soon as he said this, a number of us chimed in that we had protested the War and the bombing of Laos and Cambodia. And most of us probably had. But it was another of those sad moments on the trip, one in which we took in the enormity of what our government had done in the name of “stopping the global rise of Communism.”

What Laos suffered was primarily the byproduct of the American War. And to this day, Surya, told us, the countryside is still full of unexploded ordinance. Farmers and children are maimed and die from triggering land mines and unexploded bombs on a regular basis.

After our hike down the hill from the stupa, we went to visit the museum that used to be the Royal Palace, the homes of the former kings and queens of Laos. We were not allowed to bring hats, cameras, backpacks or purses inside and our shoulders and knees needed to be covered. Eli’s pants had a rip in the left knee of his jeans (he’s had ripped knees since he was a six-year old) and he was stopped at the door because his knee was exposed. In order to tour the museum, he had to put a pair of local pants on over his jeans, but he is so tall they ended inches above his ankles. It was a pretty funny sight but because we had to check our bags and pictures weren’t allowed, I can’t show you how silly he looked. But here’s the offending knee hole:

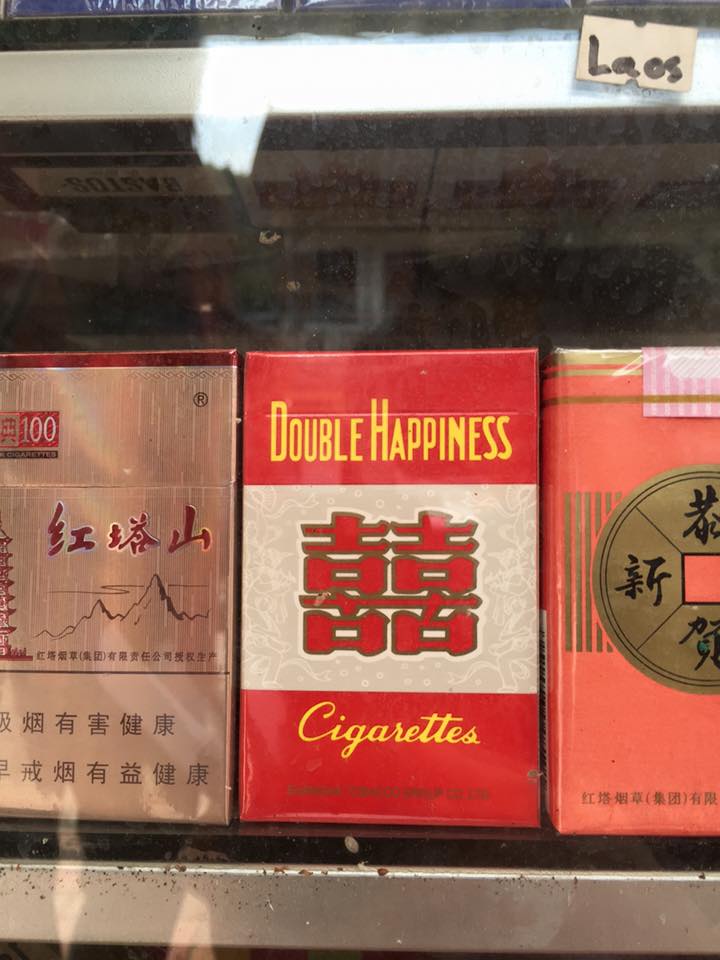

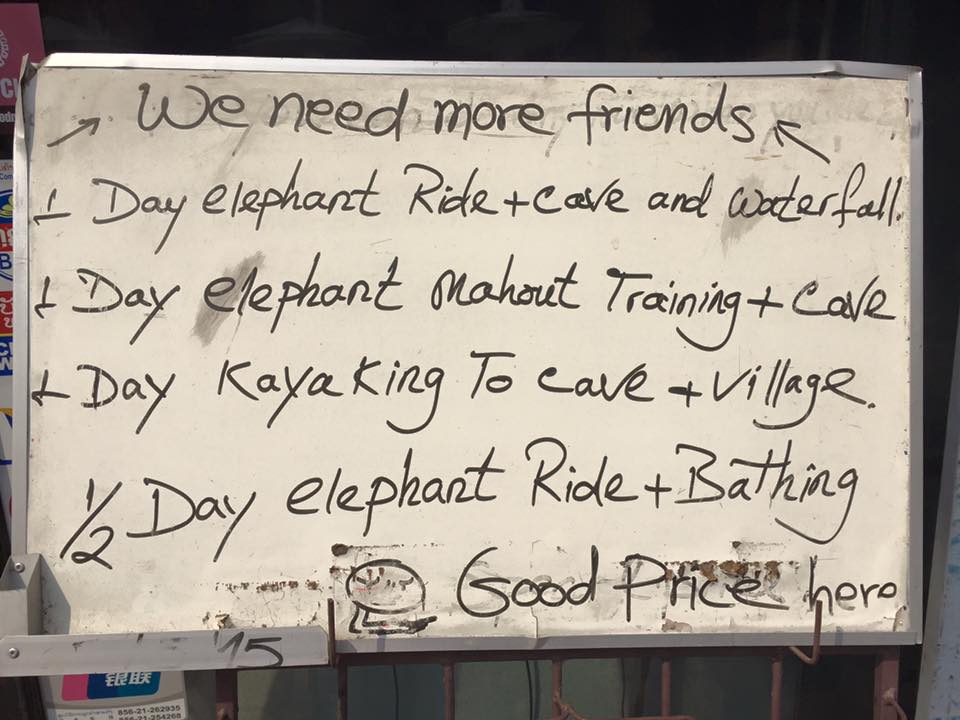

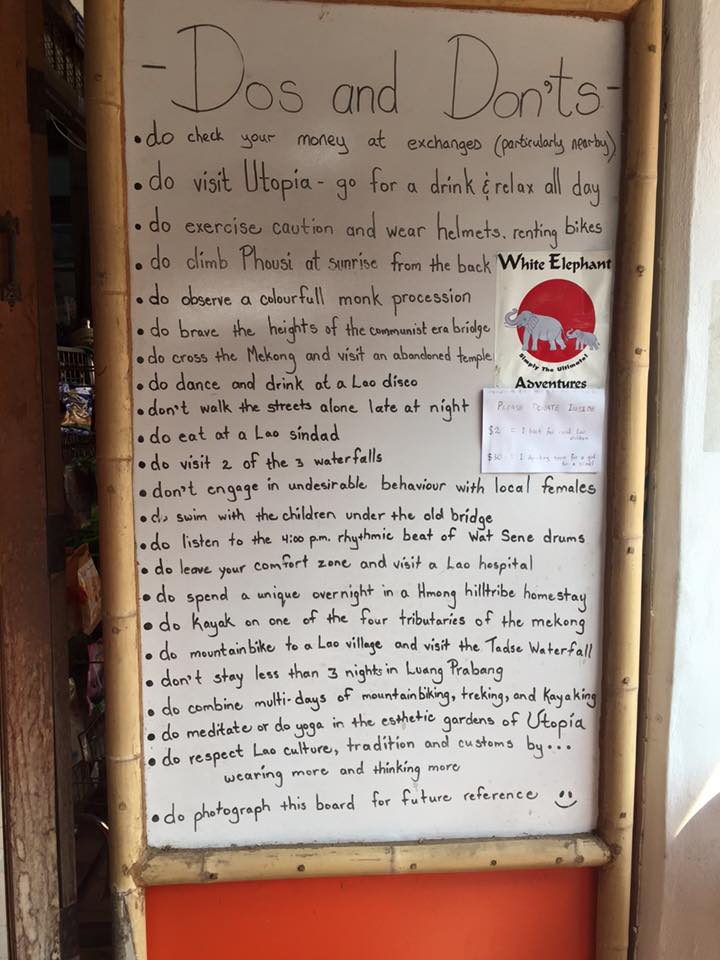

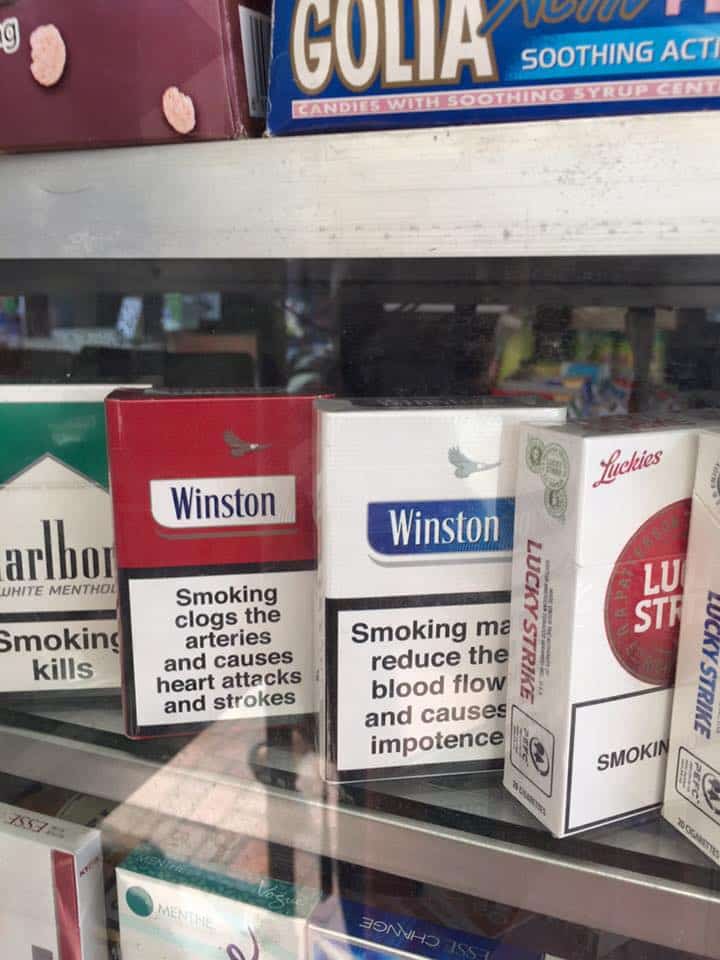

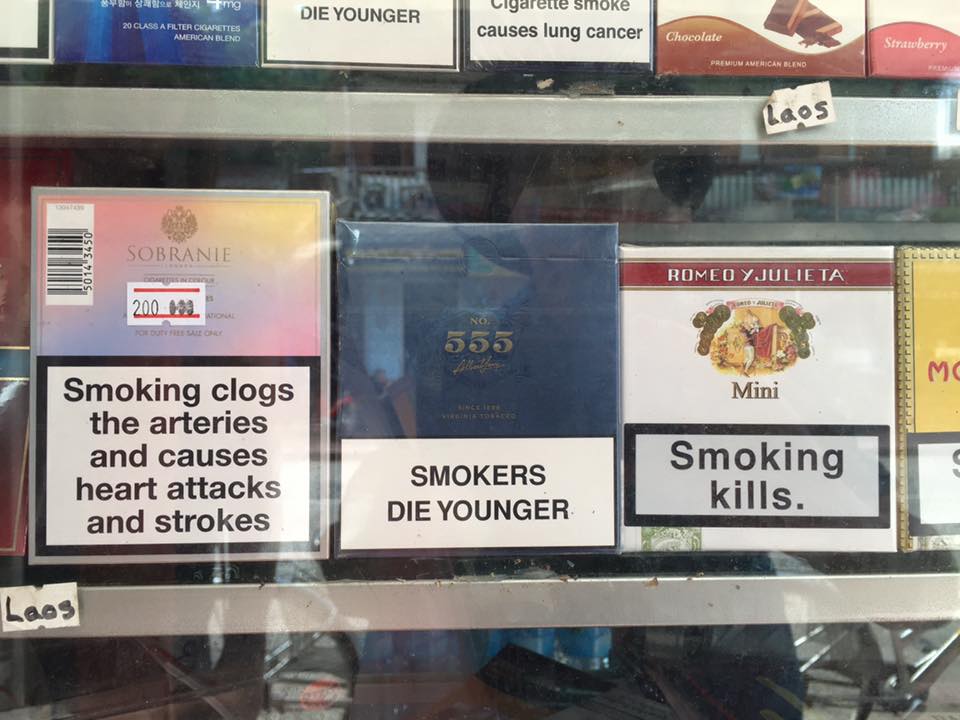

After our visit to the museum, we walked into town for lunch and then wandered back to our hotel for writing class outdoors overlooking the Nam Kahn River, naps, and whatever else people want to do with their afternoon. I spied many interesting things on the street on the way home: some very interesting cigarette packages full of extreme warnings, information about the elephant sanctuaries in this region, massages where fish nibble the dead skin off your legs (no thanks…tried that once before…a novelty, but not worth the price of admission), and a storefront that collects books and takes them out on floating library boats to children in 100 riverside villages. For many of them, it’s their first experience ever with a book.

This town is going to be very interesting to explore.

Somehow the local brand didn’t carry the same warnings: