We’ve all happily settled into our cottages at Puri Lumbung in Munduk Village in North Bali. The temperature here is at least 20 degrees cooler than it has been during the rest of our trip; the air is cool. Some of us have even pulled out our sweatshirts in the evening. I slept with socks on last night—something I never would have dreamed of in Candidasa and Ubud.

The vision of the Puri Lumbung Cottages is to create a “sensitive” tourism project that “creates a partnership between the people of Munduk with those who are concerned about environmental, cultural preservation and are dedicated to the discovery, conservation, and enhancement of the unspoiled area around Munduk.”

This hotel provides employment for the local people of Munduk and also enables them to do work that helps maintain the tropical rain forest and sustainable methods of farming. The young villagers practice dance and other traditional arts on the grounds, helping keep their cultural heritage alive.

The cottages we are staying in are simple, comfortable and border the rice fields. The view for us, as we sit on our porches writing or simply being, is the daily work of rice farming; watching the village people caring for their crop and going about their lives.

This is the view from the porch on our bungalow, #8:

I can watch the woman who sits up in a small little shelter, at the ready from her hands are a series of wires and strings that she can pull to dangle white strips of cloth, cans and bottles that clank and make noise, to keep the birds out of the crop. It is easy to get lost simply in observation of the daily work necessary to create food.

Today after breakfast, we trekked through a local plantation, through rain forest and through local rice fields. Our guides were the same two wonderful men who also led us when we were here last year: the young Ketut (who is not young, but is in his forties with a wife and two children):

And Pak Ketut, the older Ketut. Pak is a term of respect, meaning “father.” Judy says Pak Ketut is famous for having the biggest smile in Bali:

Pak Ketut had carved walking sticks out of coffee wood. We each got one to use on our hike to help with slick trails. They definitely came in handy.

The first part of our hike was up the road until we got to our starting point. From the rear of our column, I could hear Surya, taking up the rear, call out, “Are we there yet?” Everybody laughed.

After ten minutes, we came to our turn off the road. There, lying by the side of the road were long pieces of bamboo, being prepared to make the ladders workers use to harvest the cloves that grow in this area.

During the first portion of our hike, we walked up a narrow paved road that went through a locally owned plantation. People drove by on their scooters alone, in pairs, in families or at work.

The road was lined with homes and people at work in their compounds. I watched a boy in green and white shorts flying a kite in what was essentially a wind-free day. Many people were drying cloves and coffee. There was construction happening everywhere. The area looked far more prosperous than it had last year when we hiked here. Surya and Judy both mentioned it. People were adding on to their homes and we saw satellite dishes and other unusual luxuries at homes along this roadway.

Surya explained that when Suharto was President of Bali, he had a stranglehold on the major crops of this region: cloves, coffee, and nutmeg, and the farmers were terribly poor as a result. But now, with free trade, the local famers are economically much better off, and the construction we were seeing everywhere was evidence of this increased abundance. Even the dogs looks healthier. Surya said when money first came into this area, the first thing people did was improve the family temple. Only when that was done did they start making improvements to other parts of their homes.

There was incredible diversity everywhere we looked. We hiked through poinsettia, sages, banana flowers, giant avocado trees, hibiscus, roseapple, snakefruit, pomelo, starfruit, cassava trees, clove trees, golden bananas, nutmeg trees, and citronella, which is actually a variety of lemongrass.

Here’s just a few of the valuable, edible or useful plants we saw as we walked down the road:

This is what cloves look like when their first picked, before they dry and turn brown. Interestingly, the Balinese don’t eat cloves; they’re all exported for the making of clove cigarettes. The ladders used to pick cloves—which is all done by hand, is incredibly treacherous and safety equipment is minimal. Many Balinese workers are injured every year in falls from these ladders:

This is Robusta coffee, one of the two varieties we saw on our journey. The other type is called Arabica.

Surya said his mother fed him coffee from the time he was three months old. He showed the signs for a predisposition to asthma, he said, and so his mother fed him a teaspoon of fresh coffee every day, with a squeeze of lime. “See,” he said flexing his muscles, “It worked.”

This is the kind of bamboo harvested and used to make flutes:

This is what cacao looks like:

This is nutmeg:

Surya says the Balinese grate it into chicken soup and I want to try that when I get home. He also gave us the recipe for a drink to solve the problem of acid stomach after drinking to too much coffee—steep fresh nutmeg and cardamom in boiling water and drink. He says it’s a sure cure.

And these are taro leaves:

Here’s cotton. I told you there was incredibly diversity in this rich, lush landscape:

These are wing beans, one of Surya’s favorite cooked vegetables:

Every once in a while in the middle of the homes, we’d see a small warung like this one:

This was the strangest little shrine I’ve seen anywhere in Bali:

We stopped to watch two women and a man by the side of the road loading sand to be moved to a nearby worksite. This woman was laughing and joking with us as she finished filling this metal bowl with sand.

There was a lot of sand in the bowl.

Here’s the young Ketut lifting it:

And here’s Larae giving it a try.

The woman’s friend helped her lift it and put it on here head:

Surya said the bowl probably weighed about 20 kilos or 60 pounds. He said her posture was perfect to lift that weigh on her head. Then men, he said, never carry weight on their heads, they hug it to their chests or put it on their shoulders instead.

And she’s off:

Soon after we passed the woman and the sand, we turned off the paved road onto a narrower dirt track. We came upon this bamboo forest:

And this sexy looking banana plant:

A rooster and two hens were walking on the forest pathways. I guess they are the ultimate in “free-range” chicken.

For the next hour we trekked through rice fields of all kinds, in all stages of growth and harvest.

This is a fallow rice field. Farmers either let the field go fallow or plant complementary crops like yams, garlic, and shallots.

This is a rice field that has been burned after harvest:

We passed lots of running water—volcanic water used to irrigate and flood the rice fields.

We also passed white eggplant, fields of garlic, sweet potato and tiny spicy chili.

This field is full of harvested padi Bali rice. This is the ceremonial, special rice grown for ceremonies and other special occasions. It is grown on a seven month cycle and it is harvest by hand with small knives so “the transition from life to death is not so shocking.” Once it is cut it is tied in bundles and left to dry for a week. After that is carried on women’s heads back to the family compound and laid on a mat and rice is left to fall off naturally. Isn’t it beautiful?

As we stood in the field, hundreds of dragonflies flew over the rice. It was just one of those moments—you had to be there.

As we walked through the rice field, Surya explained a lot more about rice. He told us about the many different varieties and said the Balinese only eat hulled (white rice). They never eat brown rice. They think it tastes awful, and only grow some of it to serve in health food restaurants for tourists.

Surya told us about the seven different names for rice: baby rice, seedlings in the nursery are called bulih. As the rice grows in the field after it’s planted, it’s called padi (hence the name “rice paddy”). When it is harvested, it’s called gabah. And after it’s processed and milled, it’s called beras. And when it’s cooked? Nasi. Hence the dish we’ve seen on every menu in Bali: Nasi Goreng.

Selected gabah rice is used to create new seedling for the next crop. When we heard this, we asked about the GMO rice we’d heard about, and happily, Surya corrected the misinformation I’d heard (and unfortunately passed on to you) in my earlier posts. There is no GMO rice in Bali. In fact, the Balinese have worked to keep Monsanto out. In the 1970’s, Surya told us, there was IR rice, International Rice and it did require more pesticides. But it led to skin diseases in the farmers who were standing in rice fields all day. And it is no longer used.

He went on to tell us that 92% of the fertilizer used in Bali, he said, is organic and it’s subsidized by the government. The most effective organic fertilizer is made from cow dung, chopped banana tree trunks or suar leaves. But there is also organic fertilizer that is available commercially.

There is an engineered rice called C-4 which is hybrid rice which is frequently used in Bali. It is not native to Bali; it was developed in Java and Manila. But it is not the kind of rice where you have to buy new seeds each time you plant; it can be replanted. We were all glad to hear it. The other myth Surya dispelled was that Bali was not growing enough rice to feed its own people. Surya said that was not true; that Bali is a very self-sufficient economy. He did say there have been times when the government of Indonesia has tried to force the Balinese to triple their rice production to feed the rest of Indonesia—but he said that is not the case anymore.

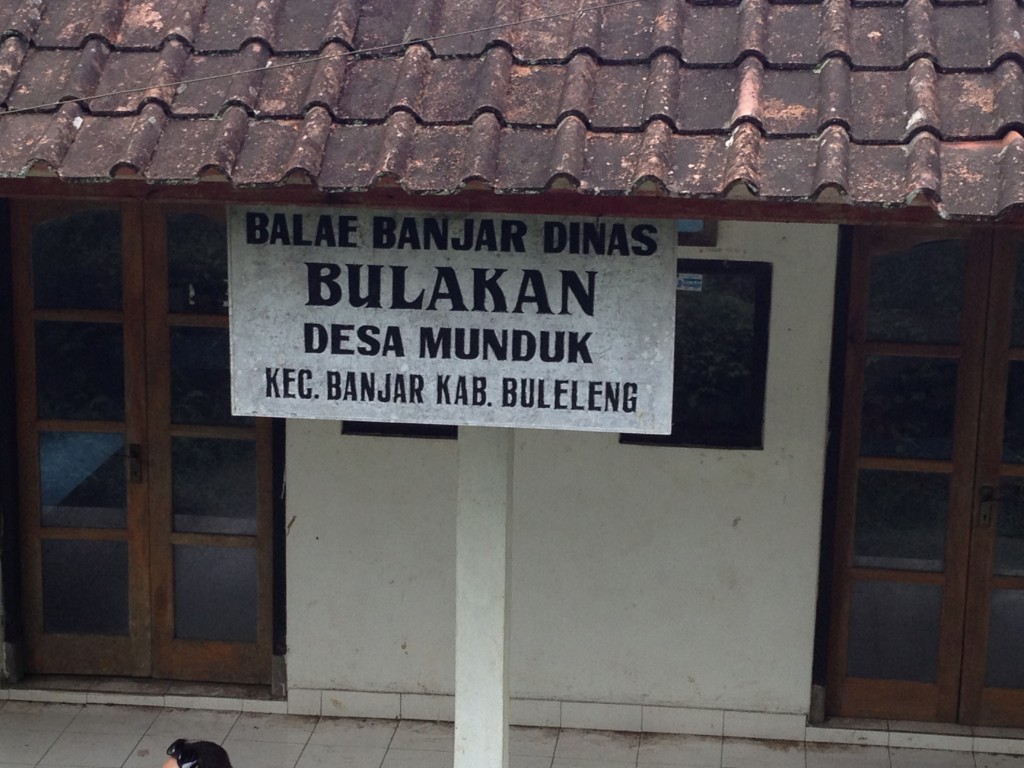

This is the meeting place for the local Famer’s Cooperative.

Next to the building is a small structure with a hollow wooden gong that was traditionally used to call the farmers together for a meeting. Even though people now have cell phones, this gong is still considered the reliable way to get the 50 households who have a stake in all that grows in this fertile land together to discuss their shared concerns.

As we made our way through narrow paths in the rice fields, following paths that led up and down and across some pretty wet, muddy, slippery places, we were grateful for the walking sticks Pak Ketut had carved.

Just after we crossed over this bridge:

The sole of Judy’s shoe came complete undone and started flapping loosely under her hiking shoe. Pak Ketut came to the rescue, pulled a piece of plastic string out from who knows where and expertly tied the flapping sole back to the shoe. Five minutes later, the same thing happened with her other foot, and he had to do the whole things all over again:

Pak Ketut looked pretty proud of himself!

Soon, we were at the end of a great trek. This was our final view of the rice field: