Back in the Istanbul airport (I learned this was a “lesser” airport for connecting flights—not the main Istanbul airport at all), when they finally posted the gate for my flight to Belgrade, I made my way there and sat on one of the hardest waiting room seats I’d ever sat upon. I picked up the novel I’ve been reading, The Bridge on the Drina, whose author, Ivo Andric, won the Nobel Prize for Literature for the book in 1961. It tells the story of Serbia, and its long domination by the Turks, from the point of view of the bridge which crossed the River Drina.

At first, as I read, the waiting room was empty, but gradually, it began to fill up—and I began studying the faces of the people readying for the flight—many of whom must have been returning to Serbia. I noticed different facial features, studied the types of shoes and clothing people were wearing, and I could sense the subtle characteristics that differentiate one nation’s people from another. Then three women came and sat on either side of me and right across from me, and continued their very loud animated conversation, giving me my first taste of the local language. I was the only American in the waiting room and I suddenly started getting very excited. I was really going to Serbia and now it was time to board my flight.

Two and half hours later—most of which I slept through, I landed in Belgrade, a city of 2 million people—the capitol of the former Yugoslavia and the current capitol of Serbia. My trip through customs was a non-event. The woman who checked my passport didn’t ask me a single question about why I was coming to her country. Didn’t ask me anything. She just took my passport, stamped it and handed it back to me. I didn’t have to fill out any arrival paperwork. I didn’t have to declare anything. I didn’t have to get my luggage checked. I didn’t need a visa. I was an American and I was in. Whisk—it was like crossing the border from California to Nevada—like I said, a non-event.

It’s strange to me how differently countries have handled my entry and exit into their countries on this trip—even when I was just passing through on a stopover. In the past week I’ve traveled through Canada, London, Beirut, Istanbul and now Belgrade. Each one was a totally different experience. Belgrade was by far, the easiest.

And when I took the escalator down to baggage to reclaim my big grey borrowed suitcase, I was in for a surprise that made this tired traveler smile. Look at what one creative person came up with:

Soon, I’d recovered my suitcase and met up with Dusica, the woman who’d invited me to Serbia to begin with. What began with one woman from her organization going on my website and reading my travel blog from Greece last May, had turned into the idea to invite me to come, which had led Dusica to write me an email, which led to several emails between us, which led to a Skype call and then another, and now the two of us were meeting face to face for the very first time. I’d arrived.

I was, however, still a bit strung out from not enough sleep the night before, so Dusica brought me to a very lovely hotel in the old part of Belgrade, the Excelsior. I checked in, took a long shower, peeled off my sweaty travel clothes, unpacked, did some hand washing, and settled in a bit before heading back downstairs for Dusica’s walking tour of the city center, old Belgrade. It’s amazing how refreshing a shower and a change of clothes can be.

My charming hotel was right in the center of the city, across from the National Museum and kitty-corner to the beautiful National Theatre, a gorgeous old building. Directly right directly behind it, a tacky, glass modern monstrosity of a Marriott (In my opinion anyway). I always love seeing that juxtaposition of old and new.

The National Museum.

The National Theatre and The Marriott.

Pirates of the Caribbean, Serbia style.

After spending six days in Beirut, where crossing the street means basically waiting for a break in traffic—and when there isn’t one, stepping out into the street and crossing one lane at a time, moving with courage and confidence and steady progression across lanes of traffic who veer out of the way, being in Belgrade with its orderly lights and timed crosswalk signals and rule-following pedestrians, all walking in unison across the street when they’re supposed to, was a real contrast, which I found very amusing.

Belgrade’s city center is full of generous wide walkways, a broad promenade perfectly designed for…well…walking. It was a beautiful spring day, warm with a slight breeze. I was perfectly comfortable in a pair of jeans, ankle boots and a sleeveless shirt. Hundreds of people were out, walking, shopping, sitting in cafes, relaxing, visiting, eating, smoking, talking—this was definitely a European city, not an American one. People here know how to sit and relax and socialize—they’re not fixed to their lists of DOING. They know how to hang out. I felt relaxed just being here.

There are dozens of outdoor cafes like this.

Broad avenues for walking.

Lots of old guys playing chess in the park.

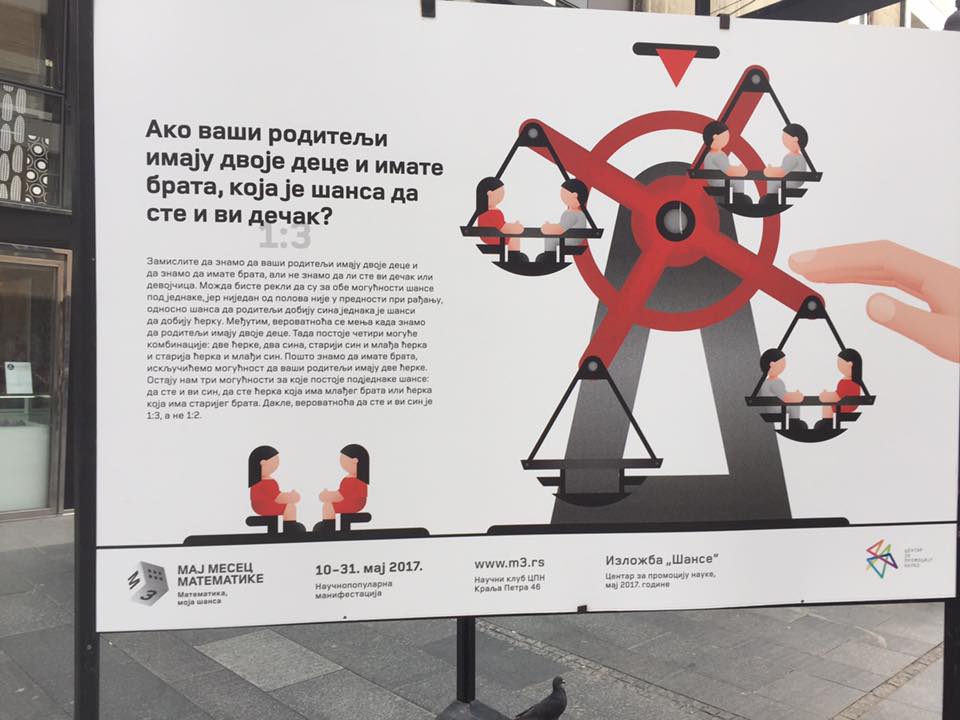

One of the first things I noticed was that the signs were in two entirely different scripts. I learned that Serbia is one of the only countries in the world that uses two alphabets. The one that looks like our alphabet, they call latinica. And the other one, Serbian Cyrillic, the “official alphabet” according to Dusica, is the one that is primarily only used by state institutions. She learned Cyrillic first as a child, but never uses it now. This sign is in Cyrillic. It’s promoting science and targets children, which is perhaps why it’s in Cyrillic:

Loved this version of a public water fountain. Where was my metal water bottle when I needed it?

Dusica eventually led me to Kalemegdan Park, a large green park surrounding a fortress build in the first century. Lilly, one of the ten co-founders of the Incest Trauma Center met us there, and the three of us continued ambling through this spacious park on a beautiful spring day, Dusica translating for Lilly when necessary. It felt easy and natural and actually quite relaxing to slow my normal pace of talking.

Here’s part of the original fortress (built in the first century):

This river, the Sava, separates old Belgrade from New Belgrade.

On our way to meet several other of her colleagues (including the woman who would be my translator for the workshop), I learned more from the two of them about the four different wars that happened in the 1990’s and the ways they still impact life in modern day Serbia. War crimes tribunals, for instance, are still going on.

Here, being an activist, means really putting your safety on the line. Two hundred gay activists marched in a Gay Pride Parade, Dusica told me, and they needed the protection of 5000 police officers—yes—FIVE THOUSAND–and even with that support, people were still beaten.

The Incest Trauma Center also encounters a strong backlash against their work—something I know well from the rise of the False Memory Syndrome Foundation twenty-five years ago in the United States just about when The Courage to Heal was really taking off.

Dusica told me that it took them 10 years to introduce child sexual abuse prevention curriculum into the schools. That just happened this year. Now, two months later, they are facing a huge backlash from churches and from far right wing fascist groups, who claim their curriculum is a manual for sex education. They insist that it’s immoral to introduce kindergarteners to the idea of good touches and bad touches. They’re calling for lynchings on social media and are agitating for violence against those who created the curriculum and have fought for its implementation.

Talk about courage. These are the women who hired me. These are the women I am going to train. I have the feeling that these women are going to have a lot more to teach me than I am going to teach them.