I first heard about the Danube River when my father played one of his favorite records on our old turntable—the one with the arm bent like an elbow that released the disc onto the base in order to play it. It was the Blue Danube Waltz by Johann Strauss. That music would float up into my dreams as I lay in bed wearing my footsie pajamas, nestled between my two long stuffed “teddy” snakes. The Danube has been drifting in my consciousness for over fifty years.

When I was little, we went on a lot of car trips, and we played a lot of car games, like competing to see who could name the most mountain ranges or cities or rivers. There was always a hot completion between my brother and me. Even though he was almost five years older, I still sometimes beat him as I eagerly chirped out the answer from the back seat of our yellow 1964 Dodge Dart, the special one with the slant six engine: Amazon, Mississippi, Yangtze, Nile, Volga, Ganges, Danube.

When Dusica asked me what I wanted to do while I was in Belgrade, I asked her for some suggestions. She suggested a tour bus (not! I’m not a tour bus kind of gal) and mentioned a few other possibilities. I asked what she liked to do and she told me about her favorite go-to walk in New Belgrade, where she lives, and I immediately said yes—that’s where I wanted to go. The next morning, I put on a pair of sneakers and jeans and a tee-shirt and Lilija picked me up in a taxi and took me over the bridge to meet Dusica. Our walk, it turned out, was going to be along the Danube.

Lilija dropped me off and Dusica and I set off along the river. In some ways, it was very much like West Cliff Drive back home in Santa Cruz—a waterside pathway full of walkers, bike riders, runners, friends talking to each other, passing time, exercising and enjoying the day. But in Santa Cruz, the ocean front is all public land and the view of the water is unimpeded by development of any kind—very different from the privately-owned beachfronts of my home town back in New Jersey.

Here in Belgrade, the start of our walk featured restaurant after restaurant floating right off the walkway, on our right. “Belgrade is number one for nightlife in Europe,” Dusica told me. I tried to imagine all these restaurants (and one big casino we passed on the other side) lit up and hopping at night. Right now, it was hard to imagine it.

As we strolled, I asked Dusica about the history of the Incest Trauma Center. It was founded in January 1994 by a group of women who’d met a couple of months earlier at a training for a hotline serving women and child survivors of domestic violence. At the training, several women began to talk about the dearth of knowledge about sexual assault. They decided to do something about it and four months later, the Incest Trauma Center was founded by ten activist women. “It was just the moment in time to understand it was an important topic.”

All ten founders had been activists already. Many had spoken out on LGBT issues. All had been active in the anti-war movements in the 90’s, standing with the Women in Black each Wednesday at Republic Square. This was back when President Slobodan Milošević was still in power—the engine behind the genocide and all the Balkan wars. Women in Black stood publicly to protest every week. They stood in silence. Surrounded by police protection, they refused to respond to taunting and threats.

I asked Dusica about the police presence, something I’d been wondering about for a couple of days, ever since she’d mentioned thousands of police protecting a small group of Gay Pride marchers. “Aren’t the police usually part of the regime and not there to help activists?”

“They were there to protect, yes, but also to control.”

Back then, the anti-war NGOs were continually attacked in the media. The women were called foreign spies, and it was claimed that they were being paid by foreign governments.

The Incest Trauma Center was one of many NGOs that sprang up out of this anti-war movement.

Dusica paused in her story to stop at the cart of an ice cream vendor. She bought me a soft serve vanilla cone—the creamiest, best ice cream I’ve tasted since the last time I had Strollo’s Ice Cream, years ago, back at the Jersey shore. As we licked our cones, we strolled down a quieter part of the Danube, where people sat on wooden benches, chatting with each other.

“Many NGOs today are no longer autonomous,” Dusica continued. “Now they are affiliated with the state.”

“There are always barriers to explaining the topic of sexual assault,” Dusica told me. There is always an opposing pressure.

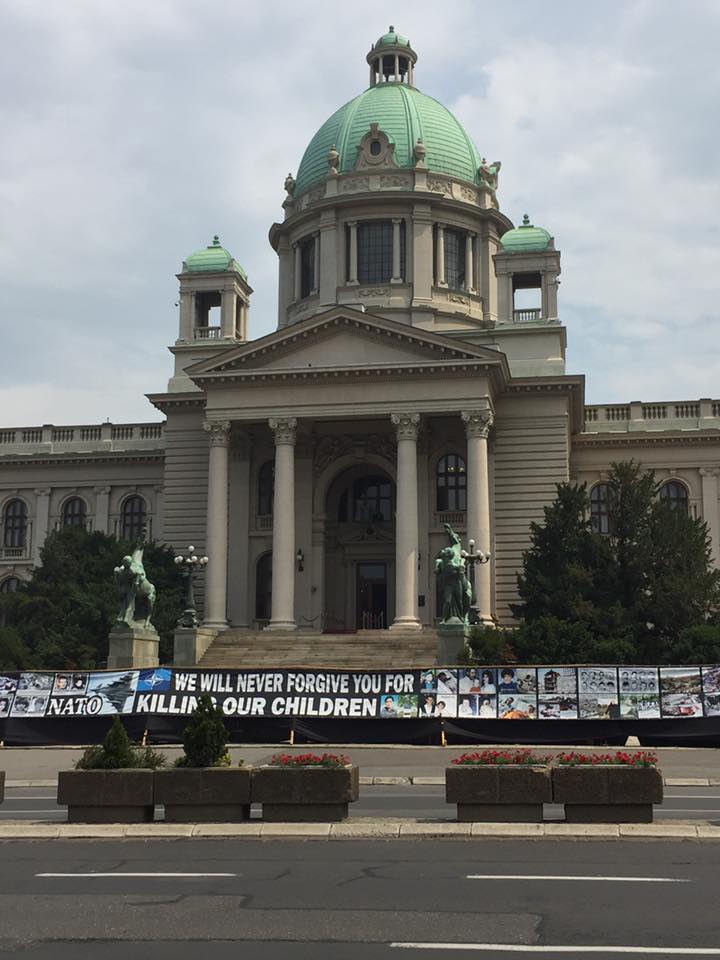

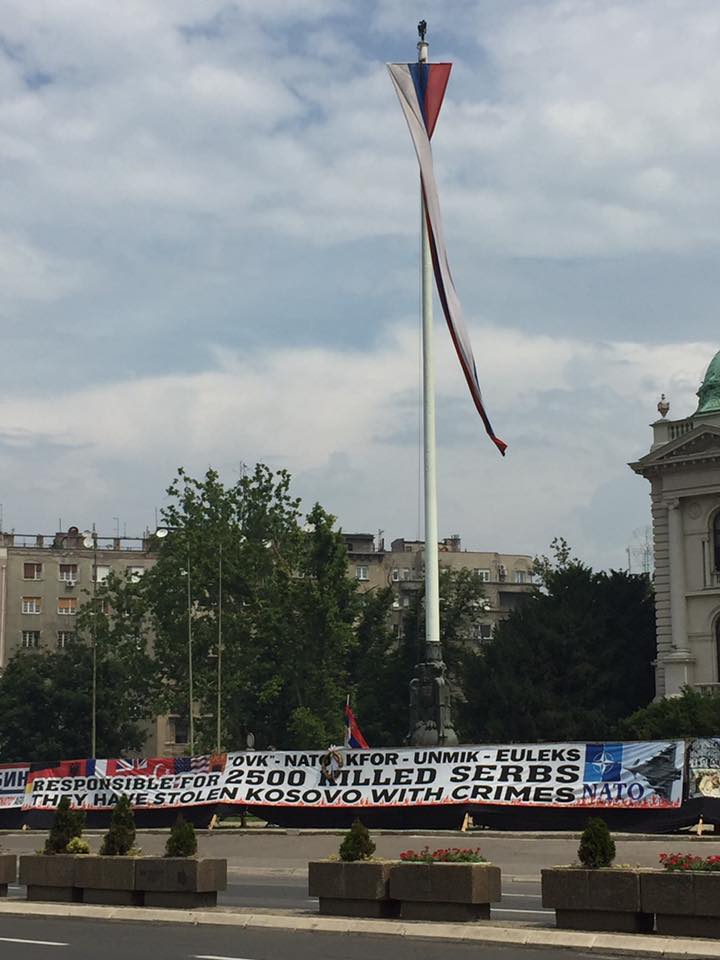

When Milošević was finally overthrown, on October 5, 2000, the Democratic opposition came to power and tried to institute reforms. And from 2000-2012, they made strides in this direction, but since then, the young democracy has been threatened by a backlash. Now, Parliament is full of the old guard, supporters of Milošević from the old regime. I could see this for myself in the signs signs fomenting divisiveness which hang directly in front of the Parliament building today:

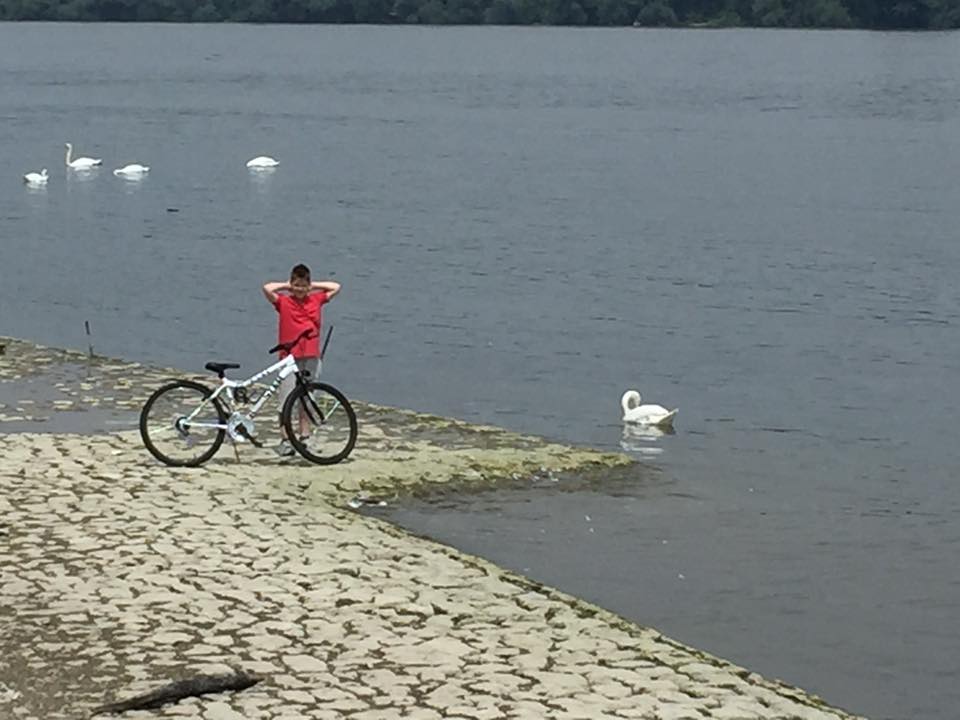

To our right, the Danube shoreline grew even quieter.

A little boy stood at the water’s edge, near a swan.

A father taught his son how to fish.

Boats floated at rest, waiting for their owners.

It was humid and my pants were sticking to my legs. Sweat was beading up on my forehead and I wished I’d brought my purple cotton bandana to wipe the sweat away. The sky was darkening and the possibility of rain electrified the air. But we kept walking until we reached the end of the walkway.

Dusica’s cell phone rang. The ring tone was the caw of sea gulls. She began a conversation in Serbian and I walked beside her, letting the sound of the words wash over me. I had no idea whom she was talking to or what they were saying. There was a freedom in that. I let sound and sensation play over me. Her conversation gave me a chance to relax into my own skin. Moments later, the phone was back in her pocket.

On our way back, I asked her more about the latest setback the Incest Trauma Center has has been dealing with—the squashing of their abuse prevention curriculum from the highest levels of Parliament.

The curriculum had been the result of five years of co-operation with the Ministry of Education. It had been implemented with the support of the Ministry, who’d said repeatedly during those five years, “Sexual assault should be on the agenda.” But after a hostile and vocal backlash from the church and the ultra right wing, the Minister backpedaled, stating that the curriculum was “not in the spirit of culture and tradition.” The curriculum was blacklisted and rescinded, just five months after its implementation.

It wasn’t just the curriculum that was attacked. The entire effort on the physical, sexual and emotional abuse of children was denigrated. Members of the Parliament who had publicly supported the initiative with praise for five years suddenly fell silent. And two women from the Ministry of Education, co-workers on this process during the five years, who had signed a statement that they supported the curriculum, were fired, and later humiliated on television. This happened within the last two months period and it is still happening now.

“What are you going to do now?” I asked.

“It’s counterproductive to respond to threats to the curriculum,” Dusica told me.

“So what are you going to do?” I repeated.

“To continue carrying a serial of civic actions ‘with a little help of our friends,’ allies from professional community and citizens who understand the need to learn about the topic.”

There was silence between us. I was taking in her story and we were both enjoying our walk and the day.

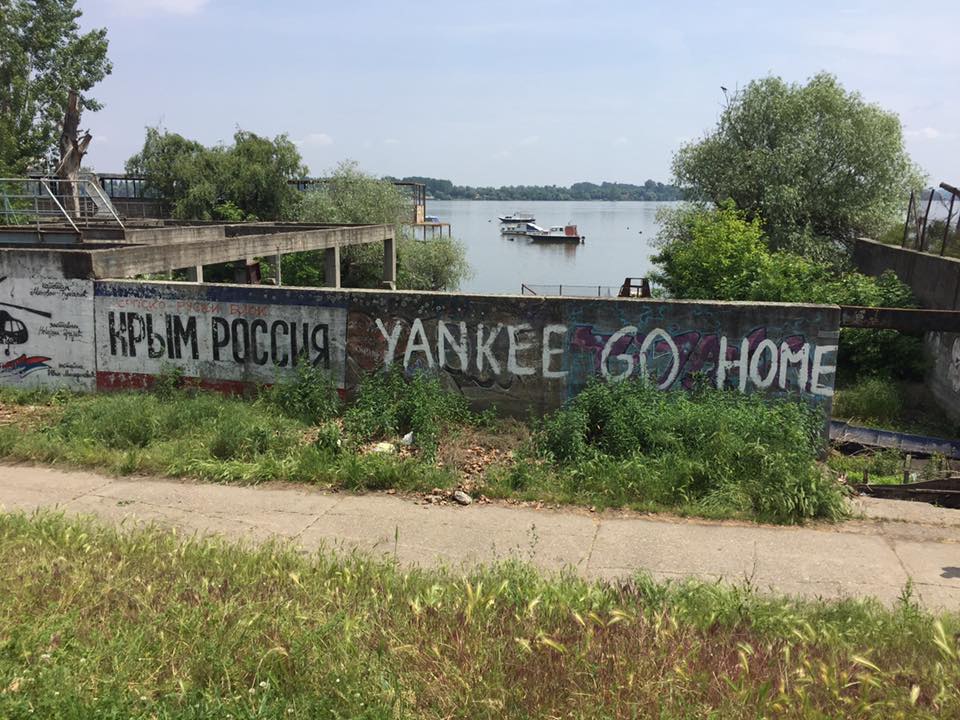

As we passed some anti-US graffiti, talk turned to Trump and what it means to resist a totalitarian regime—fighting cuts to social programs, responding to rhetoric that targets one group against another, speaking out against policies that strip away human rights–and how to sustain resistance over time. “You’ve been doing this a long time,” I said to Dusica, “and you still know how to have fun.”

“Yes, you’re useless without it,” was her reply.

Since we still had time before our 3:30 “lunch” date, we went into Dusica’s favorite riverside cafe, “Lemon Chili,” to sit in brightly colored chairs and drink tea. There was thunder rumbling over the river. It was a long time before the thunder and rain caught up with it. I kept hoping it would.

I miss lighting and thunder—it’s rare in Santa Cruz and it was one of the pleasures of my childhood. I’d enjoyed a night of it in Beirut—and now here it was again. I didn’t have a raincoat, and I was going to get wet, but I didn’t care. After a couple of years living in Ketchikan, Alaska in my twenties, where it rained 13 feet a year, rain has never bothered me.

When you write a book, you just don’t know where it’s going to lead you. I was glad it led me to this walk and this conversation on the banks of Danube. We have a lot to learn from these long-time women activists about politics, persistence, stamina and resistance.